If you hang around the morning meetings for long enough, you start seeing patterns. Diseases that appear, day in and day out, until you’re desensitized to the names.

Malaria, pneumonia, diabetes mellitus.

One of these things is not like the others.

Tuberculosis, cervical cancer, cardiovascular disease.

One of these things just doesn’t belong.

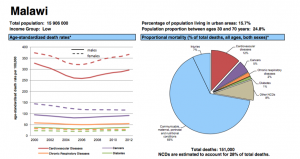

When we think about the nature of illness in the developing world, our mind tends to jump to the so-called ‘diseases of poverty’- things like malaria, TB, and malnutrition. Living in Houston or Chicago or almost anywhere in the US means that you are fortunate enough to have little exposure to these conditions. However, as my experience in morning meeting indicates, that by no means that the poor are exempted from the types of illness that typically hit closer to home. In fact, a 2011 UN report found that non-communicable diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and stroke now make up two thirds of all deaths globally (1). This indicates that a tremendous shift is occurring in the global burden of disease, to the point where the previous label of chronic diseases as “diseases of affluence” is quite the misnomer. Instead, we see that some of the world’s poorest people are increasingly bearing the burden of urbanization and global development.

This is known as the dual burden of disease, a phenomenon in which “noncommunicible diseases are imposing a growing burden upon low- and middle-income countries, which have limited resources and are still struggling to meet the challenges of existing problems with infectious diseases” (2). And what’s even more alarming is the fact that the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases is growing at a faster rate than it initially did in industrialized regions- it’s projected that by 2020, more than 70% of deaths due to ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes will occur in low-income countries! (2)

So what’s going on here? Why are people in Malawi developing these ‘first world diseases’, and how are they treated?

I think that a line from a WHO report on the dual burden of disease is most telling: “Sometimes chronic diseases are considered communicable at the risk factor level”(2). Now, if you’ll allow me to geek out, public health style, for just a moment, I’ll get to the bottom line. But first: EPIDEMIOLOGY APPLIES TO NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES. My Epi professor would be proud. Basically, what the WHO is getting at is that social behaviors are transferred from person to person, just like a cough or HIV.

One of the greatest examples of this ‘social contagion’ in Malawi has to do with diet. The introduction of low-cost vegetable oil from industrialized countries (3) has wreaked havoc on the Malawian diet, which up until recently was mostly plant-based. The ready availability of fats has pushed the country into a nutritional transition period, with an ever-increasing percentage of people’s daily calories coming from fat and refined sugar. Just walking around the market and eating in the hospital cafeteria, you can see the signs of this change: people are selling fried foods (fried potato wedges and ndas, which is basically a deep fried pancake), sugary treats (Fanta, Coke, cookies, and lollipops), and fried meat (don’t worry, Mom and Dad, no street meat for me). Although Nsima, a maize flour starch dish, remains the staple, the influences of processed foods are quite visible. And when that’s what your friends, family, and fellow villagers are eating, you tend to join in, too.

There is also evidence of genetic differences in the ways that various groups of people process calorically dense foods. Some studies suggest that many in Sub-Saharan Africa are better at retaining and storing energy from food, which is great when times are hard (4). However, when the caloric intake goes up, this predisposition backfires.

It seems like the deck is stacked against the average Malawian. Is it any wonder that 80% of cardiovascular-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (4), or that people are developing these disorders at younger ages in comparison to high-income countries?

So how are these problems being handled?

Well, in short, not that well. Chronic conditions tend to take the backseat to the more salient ‘diseases of poverty’. Combatting malaria and malnutrition seem like the first step in increasing the standard for health care. Additionally, such diseases are ‘sexier’ to foreign NGOs and government efforts. Think about it: would you rather say you saved a kid from cerebral malaria, or helped someone manage his diabetes?

In the case of diabetes (mostly Type 2), the national prevalence is up to 5.6%, a rate that’s often significantly higher in rural areas (5). 85% of Malawi’s population lives in rural areas. And guess what?!? Namitando and the surrounding enclaves are pretty much the definition of rural! A study done by the medical school in Blantyre revealed that the most common causes of diabetes-related hospital visits were complications and poor glycemic control. More than half of patients had trouble obtaining metformin or insulin (common diabetes drugs), and patients from rural areas in particular had trouble accessing refrigeration for their medications (6). Even if they had the right drugs, there is no guarantee that they’ll be able to properly manage their disease- almost 1 in 3 patients who had been receiving treatment didn’t know what diabetes was!!!

With such tasty temptations and lack of infrastructure for chronic conditions, we are well on the way to explaining the dual burden of disease. But the real kicker is that a non-trivial number of patients, some of them extremely sick, don’t even bother to go to the hospital! Poor Economics, an incredible book by Abhijit Banerjee and Ester Duflo, actually does a great job of unwrapping this particular calamity. I don’t want to share everything because 1) spoilers and 2) I’ve rambled for long enough, but one of their points is really unique in its analysis of the union between anthropology, economics, and healthcare. They explain that traditional healing has come to serve alongside modern biomedicine in the lives of the poor. In response to the tremendous economic burden of large health problems or chronic conditions, such diseases are often viewed as problems that require spiritual cleansing (7). Limb pains? Blurred vision? Frequent urination? The rural poor are more likely to consult a traditional healer to get their curse lifted than to visit a clinic and stock up on insulin. I don’t pretend that I know enough about Malawian culture to ascertain the validity of this claim at St. Gabe’s, but it definitely adds another interesting piece to the puzzle of treating patients.

(1). UN News Centre. (13 May, 2011). Countries facing double burden with chronic and infectious diseases-UN report. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=38379#.VZLj7GCJ38E

(2). World Health Organization. (2004). Developing countries face double burden of disease. Bulletin of the WHO, 82 (7), 556.

(3) Caballero, B. (2005). Nutrition Paradox-Underweight and Obesity in Developing Countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 352 (15), 1515-1516.

(4) Gersh, B.J. et all. (2010). The epidemic of cardiovascular disease in the developing world: global implications . European Heart Journal, 31, 642-648.

(5). Msyamboza, K.P. et all. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of diabetes mellitus in Malawi: population-based national NCD STEPS survey . BMC Endocrine Disorders, 14 (41).

(6). Cohen, D.B. et all. (2010). A Survey of the Management, Control, and Complications of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients Attending a Diabetes Clinic in Blantyre, Malawi, an Area of High HIV Prevalence. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 83 (3), 575-581.

(7). Banerjee, A. and Duflo, E. (2011). Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: PublicAffairs.

(8). Malawi.(2014). [Graph illustrations of age-standardized death rates and proportional mortality]. Data Access from the World Health Organization- Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles.