an excerpt from my journal…

Day 50:

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how hard it was to believe that we were halfway through this internship. Now, looking out the window of one of my four flights back home, I can say it is even more difficult to accept that our time in Malawi has come to an end.

This morning felt just like any other morning: I woke up, showered, and watched the sunrise while drinking my morning tea. Soon after we finished dragging our luggage up the stairs, Mr. Richard appeared with the bus to drive us back to the Lilongwe airport. While loading the suitcases, we joked about how it was just like the day we first arrived in Malawi, only now he would put the bus in reverse.

It was then time to say goodbye to Kabula: the kitchen where we cooked all of our meals together, the terrace where we soaked ourselves doing laundry, the place we all began to call home as time went on. Soon after that, it was time to say goodbye to Blantyre, then our friends from Tanzania, and finally Malawi.

One Week Later:

The past week has been full of quality time with friends and family. Due to the time difference between Michigan and Malawi, it was difficult to keep everyone fully updated throughout the course of the internship. As a result, I often share my stories starting from day one, using my journal entries and photos as guides to what I was seeing, thinking, and feeling. In day-to-day conversation, I’ve noticed myself begin to repeat a phrase: “When I was in Malawi…” I’ve said it while driving down the road and cooking dinner, comparing my experiences here to my time abroad. I’ve even said it while going under for oral surgery, sharing that we had gathered feedback in Malawi on a locking mechanism for the IV that was feeding into my arm.

In my downtime, I’ve also been working on finishing a book I started reading at the beginning of the internship. “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight” is a collection of personal narratives from the African childhood of Alexandra Fuller, some of which take place in Malawi. Reading through them at a time when I am also reflecting on the past few weeks has given me a lot to think about, and one quote, in particular, has stuck with me…

When describing an English guest to their house in Zambia, Fuller writes about how people like this man never last long, and then they return to their homes and say “when I was in Africa” for the rest of their lives. Coming across this similar phrase, I couldn’t help but compare myself to the foreign man. We too had spent a short period of time in another country, seen both its beauty and its challenges, and then returned to the United States to share our experiences.

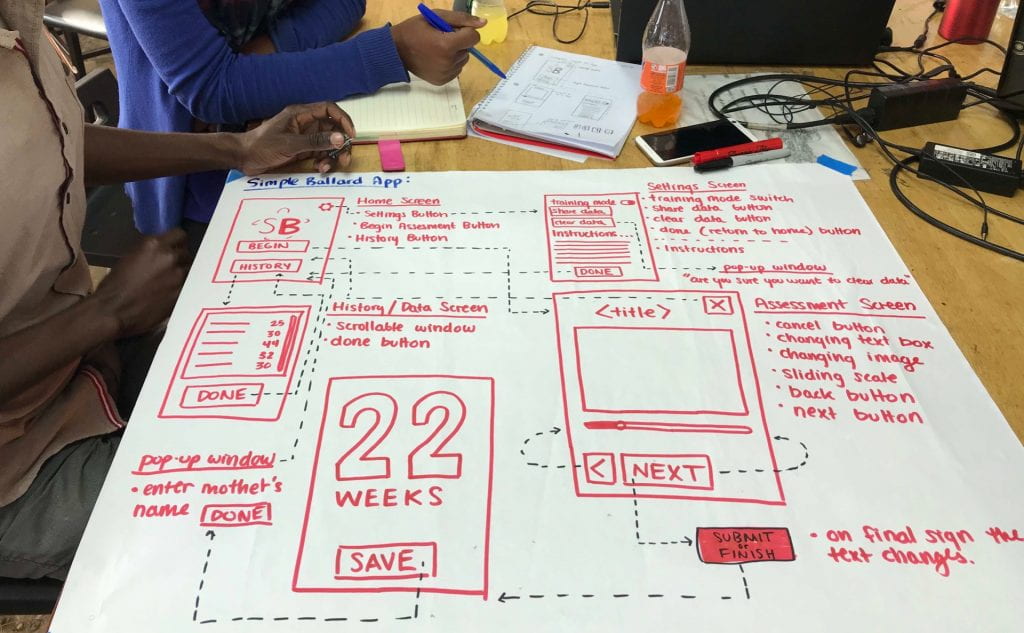

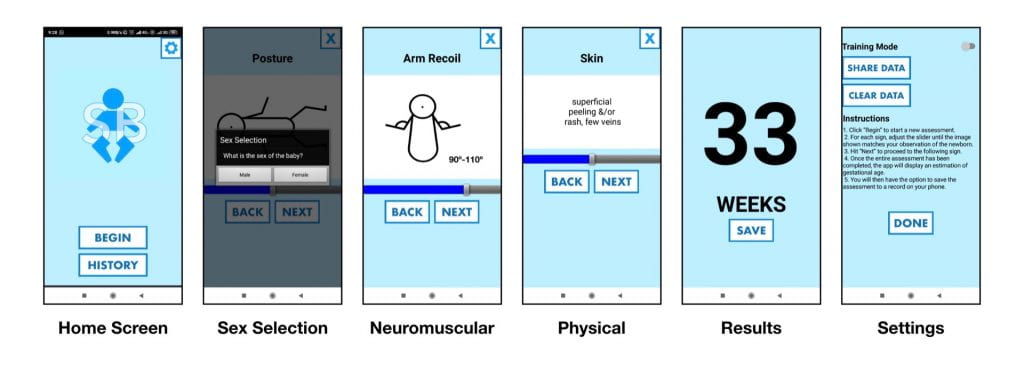

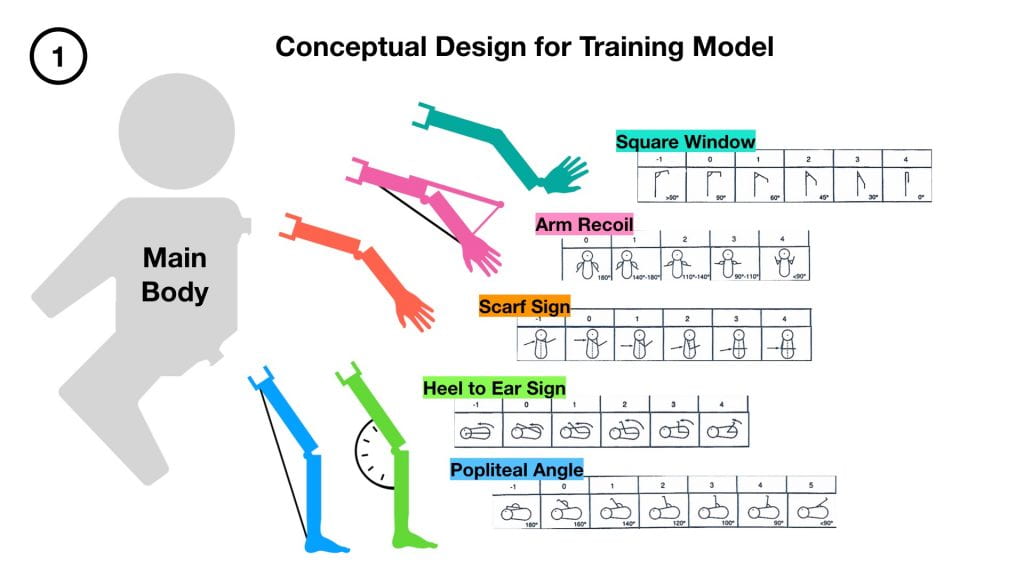

Thinking through this comparison, I began to once again flip through pictures of our work, and eventually the differences became clear. I saw our very first hospital visits, our ideas at every stage of the design process, and the final prototypes that came out of it all. Continuing to flip through my camera roll, I soon came across our speeches at the internship’s closing dinner. As I played the videos, I heard Nana talk on living with people of diverse cultures, personalities, and mentalities. Hannah highlighted the similarities between each of our lives, despite living on opposite sides of the world. Foster recounted an interview question that we all received: “Are you able to associate with people of different backgrounds?” Tebogo then gave the answer, saying that the studio would not feel the same once we all returned home.

Finally, I began to play the speech of Dr. Ng’Anjo, one of the professors who welcomed us to the design studio when we first arrived at the Polytechnic. To the room of interns from three different countries, he said, “Keep the course. Whatever you have learned, don’t just say: Oh, it was an experience. We were in Malawi … Blantyre … a lot of dust.” The room laughed. Smiling at his own joke, he continued: “Amidst the dust, amidst the noise, amidst all that you have experienced… say this is the knowledge that we got, and I’m going to run with this knowledge.”

Listening to these words once more, I am reminded that while our time in Malawi has come to an end, the experience is not confined to a single summer. The names of my fellow interns do not simply stay on the pages of my journal, they light up the screen of my phone. Despite the distance, ideas continue to flow. I receive updates from my teammates as they gather feedback from district hospitals on our training model and application. As progress is made on the MUST Design Studio, suggestions are shared from what is done at the OEDK and the Poly.

When I was in Malawi, I found something that I want to continue to be a part of for years to come. As Dr. Ng’Anjo put it: “by working on these types of projects, you serve life itself.” I chose bioengineering because it lies at the intersection of technology and people. I wrote this statement when I applied to Rice. Last year, I used it as motivation whenever I was struggling with a problem set in a physics or math class. This summer, I had my first opportunity to understand what this statement truly meant.

– Alex

I would also like to thank all of the donors and supporters of this internship program for making this possible. Without you, our newfound community of engineers from Malawi, Tanzania, and the US would not exist.