Welcome Week is over! It was a whirlwind of a week, but I think the students really enjoyed it and learned a lot along the way. I think the best part of the week, and one I hope they can continue in future Welcome Weeks, was how we incorporated a team design challenge throughout the week as a way for the students to learn about the engineering design process. Their challenge was to build a phototherapy light stand for the BabyLights that are currently used at QECH to treat jaundice in babies. This project was really cool because not only did it affect people literally a 10 minute walk down the street from the Poly students, but the BabyLights themselves were actually designed and built by faculty at the Poly. It was a great chance for the students to see a demonstrated need in their immediate community and to see how their skills and the skills they will acquire can be put to use.

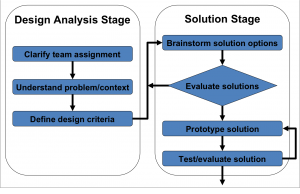

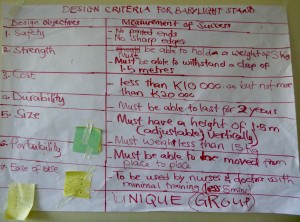

Based on some final day surveys we took, it seems like most everyone’s favorite lecture was Introducing Design Criteria. The students all seemed to have a very intuitive grasp on design criteria sort of as rules that you set for your design. We (all of the Poly and Rice interns) walked around and helped the various teams develop their ideas further with quantifiable, testable measures of success, but most of the concepts for the design criteria came directly from the new students. Here’s a picture of one of the teams that did an especially good job:

Another cool thing about the challenge we chose and the Poly’s location is that we got to take the new students on a tour of QECH. They saw PAM, Chatinka nursery, Pediatrics, and Orthopedics. It was a chance for them to see medical devices in use at the hospital and to begin thinking about the way engineers and health care workers interact. But it was also a chance for them to see the ways they could make a big impact. One of the students told me he expected to see one, or maybe two broken machines at PAM. He was shocked to see the dozens upon dozens of machines in desperate need of repair and was beginning to see how he could build a career upon it.

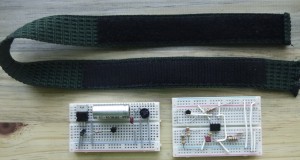

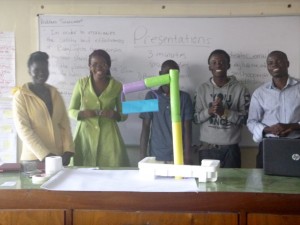

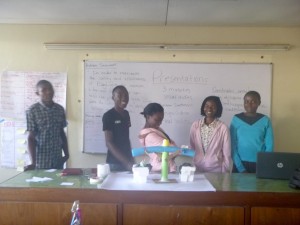

On the last day of Welcome Week, all of the teams got a chance to make a short presentation about their projects. By this point they had all prototyped a low fidelity stand, and so each of the teams was able to present on the problem, their design criteria, decision making process, final solution, and any rough iteration or testing they performed as well. It was a really great way to wrap up the week; I was especially impressed by all the questions the students asked each other at the end of the presentations and how well the teams responded.

Sarah, Emily and I are optimistic and hopeful about the possibility of this kind of orientation week continuing for many years to come, but as for this year I think we can confidently say we met our four goals of introducing the students to the Polytechnic, building a network of peers, understanding the skills necessary to be a BME and exploring some of the career options of a BME.