The weekend is over, and the safaris were unforgettable. Malawi is a beautiful country, and it’s wildlife and landscapes are both enchanting and inspiring. Of course my family was excited to hear about all the elephants and hippos, but I’m sure it’s nothing new for the Malawi blog! I would definitely recommend a visit to Majete, for anyone who finds themselves in the area, though.

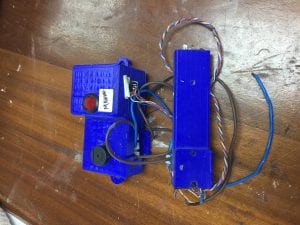

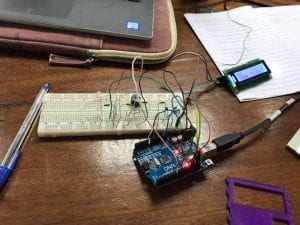

My first couple of days at the Polytechnic Institute have been full of new and exciting things. First of all, I met the Poly students who have been working together with our Rice 360 team in the design studio. Day 1, everyone was already scheduled to make hospital visits outside of Blantyre, so I joined the Mathermal and Suction Device teams and we all hopped into a minibus together, bound for two district hospitals: on the first day, Zomba, and the next, Thyolo.

This was an eye-opening experience, which cannot be fully conveyed in a few small paragraphs. We really do take so much for granted, back home. Can you imagine sitting on a hospital bed in the Texas Medical Center, and being told that your temperature hasn’t been measured because the thermometer is broken, or needed in another ward? This is only a tiny example of the challenges doctors, nurses, and patients face here. Much of the way things are done seem hopelessly guided by well-worn twin ruts of under-staffing and lack of supply. These are forces which we may know of but whose consequences are nonetheless difficult to anticipate. From a problem-solving design perspective, I feel like so many of their challenges are just assumed not to exist.

This trip broke that perspective bubble for me. In these two visits to the district hospitals, we were given priceless first-hand exposure to their daily reality. The generous nurses and staff took time to discuss things at length with us,  giving us insight into how things are done here, and what sort of environment, expectations, habits, and needs we were designing our devices for. The more we heard them speak, the more my belief in extensive needs-finding and local input grew. This sort of discussion was absolutely critical to good design! How many of my previous assumptions would have led me to miss what would be here a fatal design flaw? My time here was spent critically thinking about suction pumps and thermometers with the other teams, but I felt my perspective broadening in a way that will likely influence all of my future work.

giving us insight into how things are done here, and what sort of environment, expectations, habits, and needs we were designing our devices for. The more we heard them speak, the more my belief in extensive needs-finding and local input grew. This sort of discussion was absolutely critical to good design! How many of my previous assumptions would have led me to miss what would be here a fatal design flaw? My time here was spent critically thinking about suction pumps and thermometers with the other teams, but I felt my perspective broadening in a way that will likely influence all of my future work.

I can’t wait to see more, and to learn more. This is definitely a mental change I was seeking. It’s one thing to hear about other people’s situations, and quite another to see them and talk to them directly about it. I am very thankful for this – for having the chance to open my mind this way.

It’s time to go back to the studio and get to work. Looking forward to lending a hand.