Two weeks ago, I wrote about how important it is to get a good understanding of the context a design will be implemented in, and the user of a device. This past week on my blog, I was more focused on what qualities of a device this understanding changes. Now, I’m going to focus down even more and use a device I’ve been working on for the past few months to explain with more concrete details the nuances of global health technology design.

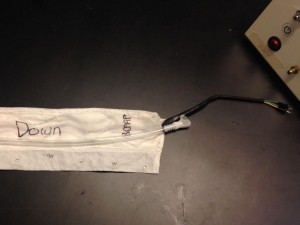

I took a Global Health Technology course this past semester at Rice about appropriate design, during which I was part of a four person team tasked with developing a heating sleeve to be used in tandem with Rice’s bCPAP technology. The bCPAP helps babies with underdeveloped lungs to breathe, and right now it supplies the patient with room temperature air; warming the air–which is what our device does–will potentially increase the survival rates of babies treated with bCPAP. Our basic design is a 9 foot long sleeve that snaps around the tubing delivering air from the bCPAP to the baby. The sleeve has heating wire sewed into it, and connects via a plug to a control box that regulates the temperature of the air delivered to the baby to 37C. Essentially the device is a long and skinny custom heating pad, made to heat bCPAP air to body temperature.

We spent about four months working on the device, and this summer two members of the team (Renata and myself) are interns in Malawi. We’ve been able to gain a much more thorough understanding of the context our device will be implemented in, and get feedback from intended users about how best to improve our device over the next year.

Through this experience, it’s become obvious what considerations we didn’t know we had to take so seriously. The thorough research we’ve been able to do has revealed flaws in our design that would bar maximally successful implementation, and has been an interesting reflective process to go through. Here is some of the feedback we’ve received, which I think shows what sorts of concerns are difficult to imagine without having visited the hospitals our device is targeted towards:

- Ability to be cleaned. Our device has current-carrying wires running through the sleeve that heat it up. This makes the device especially difficult to be cleaned, as we don’t want any liquid to make contact with the charged wires while in use. Waterproofing our device, though, is also challenging, as most of the waterproofing materials are not very thermally conductive, which makes temperature control difficult. We decided to sew a layer of nylon as the outermost layer of our sleeve, as this made the sleeve moderately waterproof but still adequately thermally conductive. Since the sleeve doesn’t come into contact with the patient, we thought this moderate waterproofing would be sufficient to allow for spot cleaning as needed. Since being here, I’ve learned that was a pretty unreasonable assumption. The bCPAP babies frequently lay on the same cot as two other babies, without any divider separating them. This means the tubing easily touches the other babies, as well as anything lying in the cot. Many of the program associates for the bCPAP clinical trials have indicated that the tubing often comes into contact with blood, feces, and other bodily fluids while in use at the district hospitals. Additionally, the tubing often is coiled up on the ground between the bCPAP machine and the patient. This not only would cover the sleeve with dirt, dust, and any other mystery liquids that lie on the ground, but also makes it susceptible to being doused with the ample amounts of mop water that is used to clean the wards, or any spilled liquids. However, we don’t want to make cleaning the sleeve a difficult process, as that would be an additional barrier to use; if there are many steps involved in attaching/removing the sleeve from the tubing and cleaning the sleeve, nurses may opt not to use the heating sleeve at all in order to save time. Alternatively, because many of the nurses didn’t grow up with electrical devices, they don’t have the same instincts concerning wires, power, and water; some nurses may submerge the heating sleeve with the electrical wires into the same bleach/water solution used to clean the bCPAP tubing because they don’t understand why not to. Finding a balance between ease of use, sterility, and functionality will be something we have to spend a lot of time with next year.

- Patient/guardian perceptions. One of the difficulties currently facing the bCPAP clinical trials is how the mothers, especially in rural areas, perceive the machine. It can look scary to mothers due to the apparently invasive nasal prongs, and there’s been a lot of talk about how to best get mothers “on board’ with the device. Some have expressed concern that the sleeve covering the bCPAP tubing would make the mothers more wary of the bCPAP, as they cannot see into the tubing delivering air to their child—she wouldn’t know what was in the tubing. The color of the device was also frequently discussed with nurses and the program associates, trying to determine which color is the most comforting to mothers.

- Weight. We were aware of the fragility of the babies treated with bCPAP, and knew this meant our device had to be lightweight. However, we figured that the tubing would be resting on the bed or on a table nearby, so the weight of the entire 9ft tubing + sleeve wouldn’t be tugging at the baby’s face. As a result, we were initially satisfied with our heating sleeve weighing 195g, which is about as much as the tubing weighs. However, being in the wards and watching the device in use has changed that assumption. The babies treated with bCPAP are often resting on beds a meter up from the ground, and the bCPAP tubing I saw often draped directly off the bed towards the ground. This means the weight of 1 meter of the tubing (and possibly in the future, the sleeve) is tugging at the patient. Since the neonates are already so tiny, and their skin so delicate, the added 195 grams of our sleeve would make a significant difference. Over the next year, we will have to work to bring down the weight of this device significantly.

- Other unforeseen difficulties. One medical student had noticed that in the special care ward, there were many bugs that flocked to the oxygen concentrators, as they heat up during use. While bugs aren’t too common in QECH, they are in the district hospitals. Since our entire sleeve gets warm and is often laying on the ground, we realized this may be a big problem. We’ll have to figure out how to heat the air without making the outside of the sleeve warm, so as not to attract any unwanted visitors.

In addition to these notes, I’ve gotten feedback from various doctors about what testing they think is necessary to run before the heating sleeve moves forwards. While these changes and tests will be difficult to navigate, understanding the potential barriers to implementation of our current device while we are still early in the design process has been lucky, and hopefully will significantly improve the chances our device has for long term success.