I find it hard to believe that we only have a few days left in Malawi. This past weekend, we said goodbye to our good friends, Katharina, a German doctor who had easily become our closest confidant, Suave, the Palliative Care Clinical Officer and our unwavering supporter, and the Grey’s, whose generosity and good-nature have left an indelible mark. Our departure becomes more real by the day. However, with that being said, we have had many activities to keep ourselves occupied this last week. We were recently tasked to go to three CHAM (Christian Hospital Association of Malawi) Hospital’s near Lilongwe to gather maternal and child birth data. Beyond this, we continued our work on Morphine Tracker. Also as I skipped out on blogging last week (whoops!), I’ll also briefly describe our experiences building the Ob-Gyn Stirrups with local shops and personnel – yeah that’s right, 3 topics in 1 blog.

Collecting Data from CHAM Hospitals and the Pumani bCPAP Study

The Pumani bCPAP (Bubble Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) is a student-initiated technology that has been expanded to all central hospitals and 14 district hospitals in Malawi. This system, which generates flow and utilizes a water bottle to adjust pressure, can deliver ambient air/oxygen to babies, particularly pre-terms, suffering from respiratory failure, a leading cause of neonatal mortality. With its success in reducing mortality, overall low cost (a few hundred dollars versus multiple thousands) and greater durability, Rice hopes to magnify its impact through implementation in CHAM hospitals. Our role as interns is to gather data about child births, delivery methods, newborn complication, etc. to assess what the needs of the particular hospitals are, if the Pumani bCPAP would provide benefits and if so, how many machines would be required. Personally, while the recording was tedious, it was still a great feeling to be able to contribute to such a large effort. Moreover, having spent so much time at St. Gabriel’s, it was interesting to see other CHAM hospitals. Unfortunately, that also meant a few extra days on the road instead of enjoying our Namitete-home a tad bit more. One random lesson I gained from this experience was how challenging it was to plan our trip’s agenda in a foreign environment. Things don’t work as they do in the States, where you can easily schedule a specific time and then pop in and take care of business. Proceedings occur here in Malawian time and style; it was a real cultural experience trying to navigate this system while still maximizing our limited time.

Morphine Tracker: A More-Phriendly Method of Data Collection

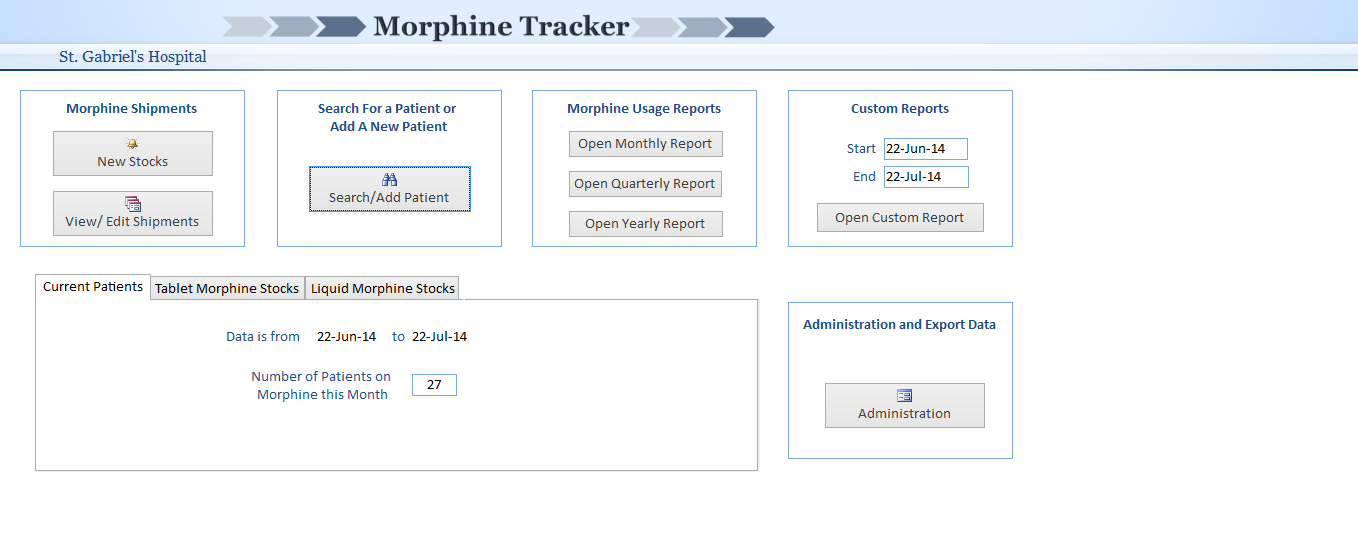

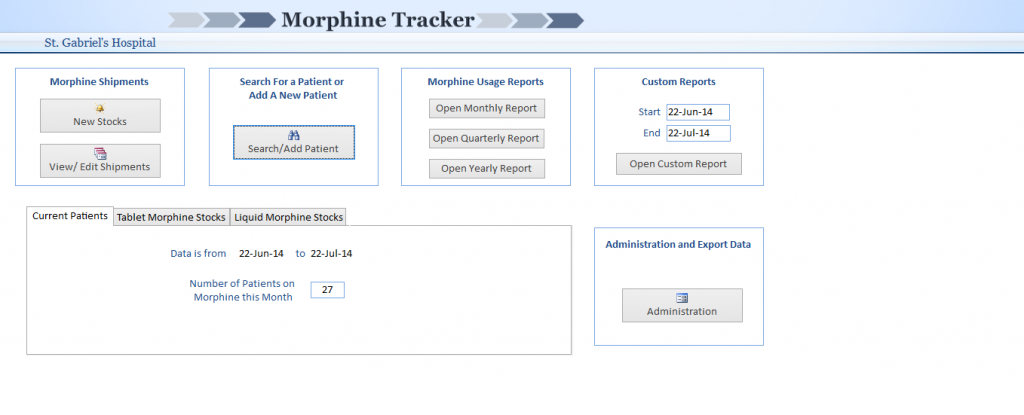

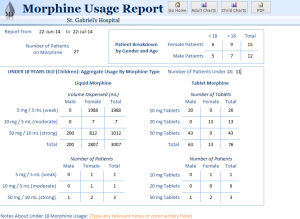

Morphine, a potent pain reliever for severe conditions, is highly regulated and heavily monitored by the Malawian government. Often the government calls or asks for reports regarding the number of patients currently on this drug, the amounts used, etc. However, due to the current method of manual recording, this often takes many days to compile. Furthermore, there is a disconnection between the needs of the population for palliative morphine use and availability of stock. For example, the hospital was without morphine for multiple monthly periods this past year. By integrating a tracking aspect to the database, where the user is warned upon “low” stocks of this drug, this system can more effectively alert health professionals prior to complete exhaustion. This higher awareness can possibly improve resource allocation and distribution. Moreover, this tool provides quick and easy metrics such as total patients using various morphine strengths/types, the totals consumed in periods of time, specific dosages for different patients, etc. We hope that Morphine Tracker has the potential to improve morphine reporting function and improve data accuracy and timeliness.

We had a chance to demonstrate this electronic medical record (EMR) to the Palliative Care Association of Malawi in Lilongwe to understand the needs and gather additional perspectives on the system. Moreover, we implemented the program on a pilot basis at two palliative care centers in Malawi, St. Gabriel’s Hospital and Ndi Moyo. Joao ventured out to Salima, Malawi yesterday for this very purpose while Truce and I toiled away at a hospital collecting data. There’s definitely excitement to see how this project pans out in practice; however, it is important to recognize the challenges in transitioning from concept to used product. First, the information flow begins with the original paper booklets at the pharmacy and then later, involves input in the computer. However, two specific criteria, age and gender, are not included as part of the Ministry of Health ordained morphine usage book. These two aspects, especially age, were described to us by clinicians to be of essential value, yet were not even recorded. In addition, age serves as a huge analytical criteria in Morphine Tracker. We were faced with a system that incorporated more tools, but was incapacitated without the information. This forced us to backtrack and add these fundamental values into the original data collecting method. Further issues to consider have included computer literacy, commitment to record keeping, and training, to name a few. There are so many factors to think about regarding adoption and future effectiveness; however, the enthusiasm that we have garnered through Morphine Tracker pushes us onward through these obstacles. Special shout out to Truce and Joao for their absorbed dedication to ensuring the best product possible! While our time is limited, we believe that this database can eventually help many other clinics in Malawi and beyond. It’s up to next year’s interns to use the feedback and information received to further improve this EMR and use the ties formed this summer to continue to expand the system incrementally.

Ob-Gyn Stirrups: Additional Functionality to Hospital Beds

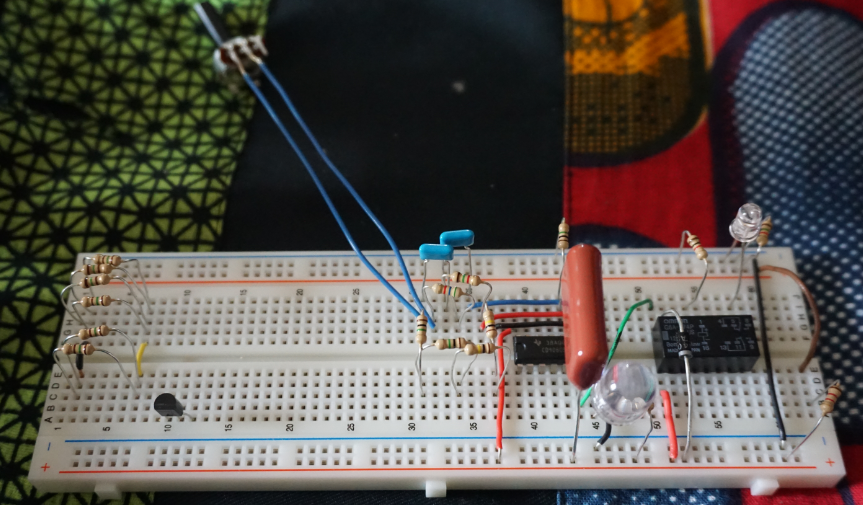

The Ob-Gyn Stirrups were originally designed for traveling physicians from developed countries to conduct outreach pelvic exams. They include portable stirrups, curtains, lights and stools, forming essentially a moveable examination room. This is particularly effective in reaching the vast majority of females in developing countries, in fact over 90%, who have never had such an evaluation. This physical assessment can be instrumental in diagnosing cancers in early stages, detecting infections and finding other problems. However, the Ob-Gyn Stirrups’ transportability had little influence for St. Gabriel’s, which does not engage in such outreach clinics. It does, though, promote pelvic examinations by adding functionality to hospital beds, which often do not allow for such clinical assessments. Made of a wooden framework, a crank that tightens it to a flat surface and cloth-based cushions for the feet, this project utilized widely available resources to uniquely address this issue. Having had a chance to work together with local stores, namely, the Namitete Furniture Shop for the framework and a local bike shop to mimic the tightening mechanism, to create a Malawi-made version really emphasized that solutions need not be complicated to be influential. While I’m not sure to what extent the hospital will maintain and use such ties to create more stirrups, it serves as a proof of concept that this solution can be locally manufactured to address a local challenge.

Concluding Remarks

Well, that summarizes the many internship related tasks that have consumed and taken up our current time here in Malawi. I promise that the next post will be short and fun. See you all in a few days!