It’s been four days since I returned home to Prosper, Texas, USA. People keep asking me if it feels weird to be home. I think people expect me to say something along the lines of “Yes, of course! Everything is so different! What a strange feeling!” And it’s true that lots of things are different. I’m readjusting to driving on the right side of the road. My family and I stopped at Buc-ees on the way from the Houston airport to my hometown near Dallas on the day I got back to the states. For those non-Texans who are unfamiliar with Buc-ees, it’s basically this massive gas station general store. It has every gas station snack you could ever imagine, times ten. I was sleep deprived from over 45 hours of travelling at that point, and I almost had a meltdown when my sister walked my half-asleep self into the Buc-ees. It was something to behold. I had forgotten how absolutely massive stores in the US are. The sheer number of options was unsettling. Another area where the differences particularly struck me was this morning when I went to the GP for my yearly doctor’s check-up. After spending weeks growing used to the state of hospitals in Malawi, the cleanliness and abundance of technology and resources in my GP’s office really struck a chord. As the nurse took my blood pressure, I stared at the mobile BP machine and all I could see in my mind’s eye were the dozens of mobile patient monitors sitting broken in PAM facilities that I visited over the last two months. She took my temperature and all I could think about was the lack of temperature monitors in the labor wards at the hospitals we visited and how nurses often resort to using the back of their hand to guess if a patient has a fever. There are so many differences, and it’s important to recognize them and talk about them.

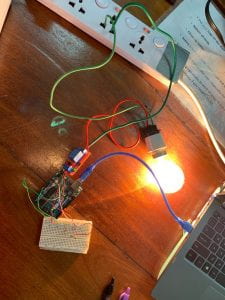

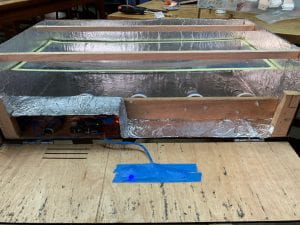

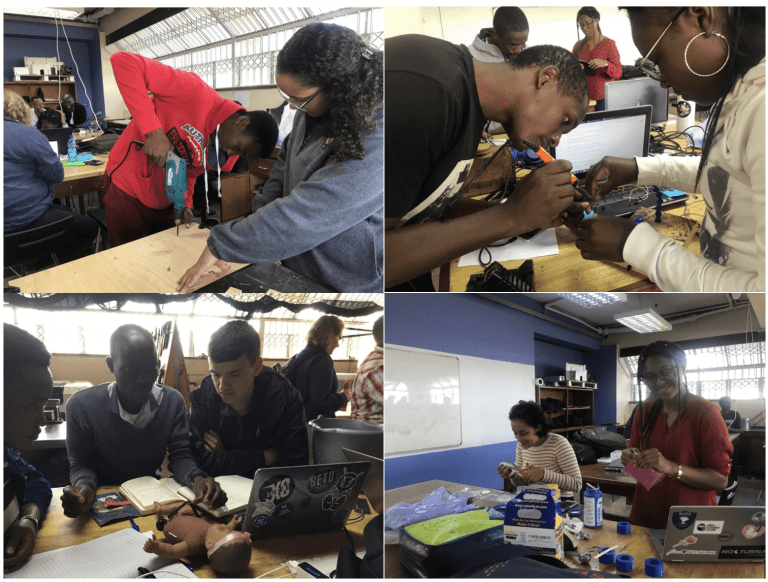

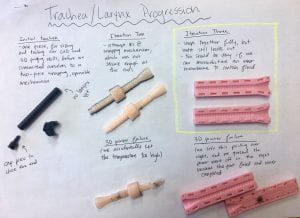

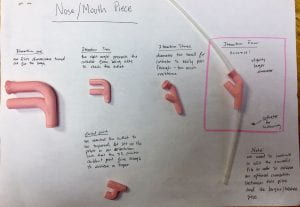

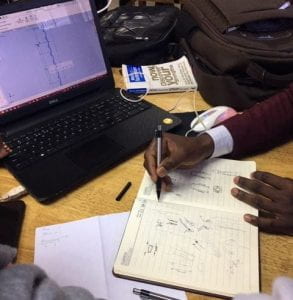

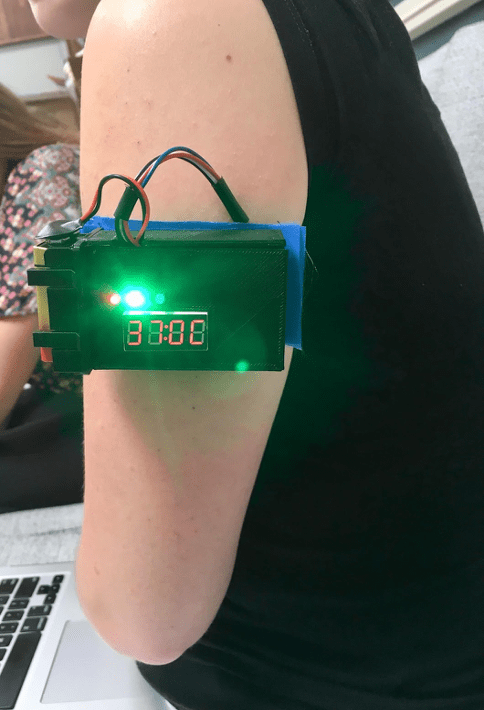

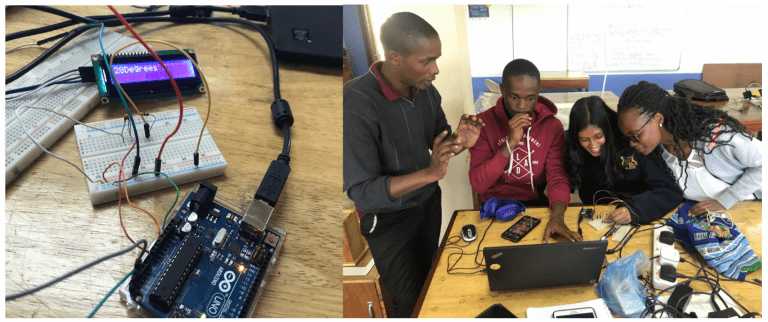

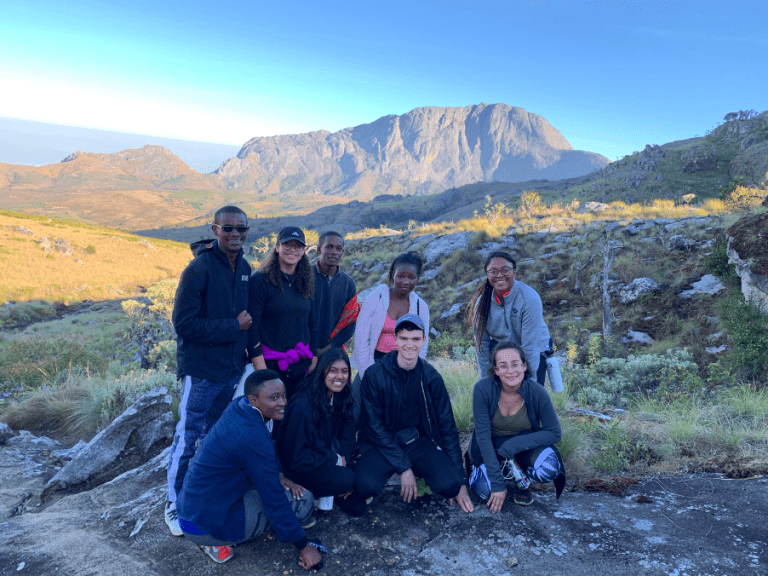

It is important to talk about the differences between our two countries. It is true that I will move forward being eternally more grateful for all that I have in this amazing country I was lucky enough to be beorn in. I will never again use random and obscure electrical components from the OEDK without thinking about how the Poly Design Studio didn’t have access to a pulse sensor for Nimisha’s team to complete part of their prototype. I will never walk into a hospital or doctor’s office without remembering the babies wrapped in chitenge in the neonatal ward of Queens Hospital. But what I think is a more important thing to say after this experience is not so much how different Malawi and the US are, but actually how we are both the same. While some differences are critical to speak about and deserve attention, most differences are illusions. During our last week, we had a really fancy dinner with our boss, all the interns, a handful of professors at Poly, and people who work in the design studio. Our boss asked one intern from each of the four universities to speak to the whole group on behalf of our cohorts: What had our experience been like? What did we expect coming in to the internship, and what did we take away at the end? It ended up being an emotionally charged moment. All four people who spoke talked about how in the beginning they were afraid that it would be difficult to relate to people from other countries, but how working with and becoming friends with all the interns was actually so easy. Everyone spoke of learning from each other and growing close to people they feared they’d never relate to. I am so, so sad to leave these friends behind. In Tebogo’s speech, he looked right at the US interns and told us “The studio is going to feel empty without you.” I almost cried.

Dr. Ng’Anjo spoke towards the end, and he told us that we shouldn’t let this internship just become an experience in our past. We should keep talking to each other, and we should make sure this week is not the end of something small but the beginning of something great: careers that transcend borders and save lives with technology. He told us to keep talking to each other, because we understand each other and the unique challenges that engineering students in the global health field face. Twenty years from now, we should be reaching out to our friends in Malawi and Tanzania to work together to start startups, help each other network and get jobs, to work at as team on the next generation of medical innovation. More than that, though, I know I will hold these friends in my heart forever, a shining testament to the fact that yes, there are differences between the US and Malawi, but at the heart of things, people are all people. For the many, many people in this world who grow up in homogeneous, small communities, it can be hard to internalize the sameness of people from very different places. But, for people making careers out of global health, or heck, even people just watching the news and voting in elections these days, it is so critical to remind ourselves that the same friends and family in our own backyards who we’d all fight for are the same as people all around the earth, and it’s important to fight for them, too.

Zikomo kwambiri, Malawi, and I will see you again.

Zikomo (Thank You), Everyone

I’d like to thank the generous donors of Rice 360 for making this internship possible. If it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t have planted a small part of my heart on the other side of the world, and I will always be grateful for that.

I’d also like to thank all the staff members and professors involved in Rice 360 and the Polytechnic for your support and guidance throughout these weeks and beyond. It is because of your investment in education that us interns are empowered to shape our lives into careers that might change the world. Thank you for believing in us.

To the Malawian interns: Racheal, Maureen, Foster, Boniface, Christina, Chisomo, Tebogo, and Rodrick: Thank you for showing me your country. Thank you for becoming my friends. I know many of you are graduating soon, and I wish you the best of luck with your future careers. I know you’ll all do great. 😊

To the Tanzanian interns: Nanah, Betty, Cholo, and Joel: Thank you for being so much fun to live with for seven weeks. It was wonderful getting to know you all and exploring the country of Malawi together. I know our many inside jokes and memories will last a lifetime. Keep in touch. <3

Finally, to my fellow Rice interns: Nimisha, Alex, Shadé, Sally, Kyla, Liseth: It was such an honor to get to know you all better than I did before. My life is much brighter now that you’re all in it. I can’t wait to keep learning alongside you. See you in two weeks!