Again, I write to you surrounded by huge piles of clothes and miscellaneous supplies that, this time, are being unpacked from my overly stuffed suitcases. After the exhaustingly long series of flights, I’m finally back home with my family in DC. I had meant to post this right before we left Namitete, but the slow internet lost to my sleep deprivation. It was bit bittersweet leaving Namitete—I’m excited to be home and see my friends and family, but on the other hand, I’m going to miss Malawi and all the friends that we made here so much, and I don’t know if I’ll ever be back.

I’ll miss Katharina—our German doctor friend who lived with us at the Zitha house; her constant friendly presence turned our little threesome into a foursome. I’ll miss Aaron—the owner of Namitete’s bakery, who gave us our first tour of the village and has been our good friend ever since. I’ll miss Suave and Alex—the two people in charge of the Palliative care ward, who served not only as amazingly helpful mentors, but also as dear friends. I’ll miss Annie—a community health worker who lived at the Zitha house; she taught us how to cook nsima and always felt more like family than anything else. I’ll miss Barbara and John Gray—the couple who owns the Duck Inn and welcomed us into their home and lives with open hearts. I’ll miss so many others that I’ve had to privilege to get to know during our time in Malawi; it was such unbelievable experience!

But enough with the gooey sentimentality; I don’t want to get even more emotional right after leaving. So lets talk about something a bit more light-hearted: all of the semi-embarassing incidents that I stumbled myself into while in Malawi. Most of you that know me have probably realized by now that I’m not the most put-together person. Or the most coordinated. Or the most organized. So its not too much of a surprise that there have been many ‘flops’ during my time here. So with that in mind, I put together a list of my top ‘flops’ during our time in Malawi:

1) Flooding the Zitha House. The water goes off in the Zitha house about once a day, usually (unfortunately) right around lunch. On one particularly desperate day, I really needed to wash my hands but the water was out. So I tried all the faucets in the house, including my shower. Apparently I didn’t close the shower tap all the way, because I later learned that if you do that, the house becomes partially flooded under a couple inches of water. So a couple others and I spent about an hour wiping up the mess of my creation. My room was the most flooded, so I also spent to rest of the day washing clothes (they were all on the floor).

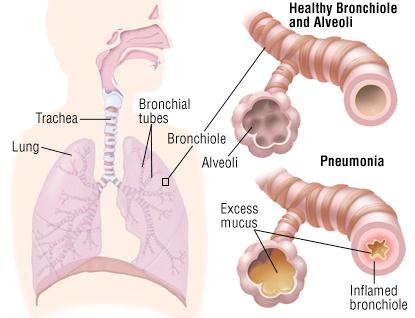

2) Buying mystery fruit. On one particularly busy market day in Namitete, we were wandering around, and I saw (what I thought was) a nice large pile of limes. Thinking that we might need some in the near future, I bought some for the very good price of 20 kwacha each (about 5 cents). Fast forward a couple of days, and we were craving guacamole. We cut everything that we needed to: the avocados, tomatoes, onions and peppers. And then I cut open the limes I bought, and it turns out they were actually something more like oranges! I didn’t feel so bad about this flop though, because when we sent Jesal out to get more limes, he came back with the same lime-orange things. But even though they weren’t what we expected, at least they were really tasty!

Looks like a perfectly good lime right? Nope! Its an orange.

3) Wearing black pants. The dirt in Namitete is kind of this really fine, reddish-brown dust that seems to find its way into everything. Usually I wear khaki pants, so the dust blends in really well. However, one day I had the not-so-smart idea to wear black pants. Let’s just say that my pants weren’t so black at the end of the day (I also got a few laughs from the neighborhood kids). Take note interns of the future!

4) Calling two different taxi drivers. As I’d mentioned before, during our second weekend here, we went up to Lake Malawi and met up with the Blantyre interns. Long story short, I was apparently really bad at telling the difference between Malawian cell phone numbers, and I (with the help of Jesal) accidentally arranged for two different drivers to take us to the lake. So when we were heading to Namitete (on the bike taxis) to get picked up by one of the drivers, I was really confused when I had another person call me and say that they were at the Zitha house. When we met up with him in Namitete, we tried to insist that we already had a driver. But we soon found out that we had half-negotiated with him and half-negotiated with the other driver; which explained a lot in retrospect, especially since every time he called back, he seemed to change price! Even though it was a bit frustrating, we all had a good laugh about it at the end.

5) Leaving laundry out for two weeks/ leaving out laptops and wallets. I don’t think this is particularly bad, but Jesal and Truce have constantly chastised me for it. I have a tendency to leave my things out where they probably shouldn’t be, like forgetting that I left my clothes in the laundry room for two weeks (I was beginning to wonder why I had so few clothes left). Also, I had a habit of leaving my laptop and wallet in the living room all night, next to an open window. In a bigger city like Houston, it would’ve been snatched up the first night, but thankfully, the rural areas of the country are known to have considerably less crime.

6) Sitting in the dark for 20 minutes. The lights in Namitete go out every couple days, and on one of those nights, I was just sitting in my room with my just laptop and my headlamp (they look really dorky, they’re so unbelievably helpful!). At one point, I heard some clamoring outside my door, but I didn’t think much of it. About twenty minutes later, I noticed a small sliver of light peeking through my door. Apparently I had been sitting completely in the dark, when the lights were already back on, for about 20 minutes. This wouldn’t actually have made the list if it was isolated incident, but then if I said that this was the only time that this happened, I’d be lying pretty badly.

Those were just a couple of the many little incidents, trip-ups and flops that happened in Malawi. But even though there will always be things that make an experience less-than-perfect, we can always learn from them and have a good laugh about it afterwards! I’ll come back and post one last time next week after having time to reflect on this whole experience, and when I’m (hopefully) no longer completely confused on which time zone I’m in.