In Malawi, the prototyping process is hard.

In the United States, it is a lot easier because if I need a part, I can just order it online, and there will be a package on my desk in the next few days. This is especially important during prototyping when you are pursuing several design options and you might need to reorder a few components. The OEDK is especially helpful because there are so many materials at your fingertips to try out and experiment with.

(Me holding up a sample of the parts we ordered from Mouser)

Prototyping is really hard in Malawi when most manufactured components have to be specially imported. Not only does this ramp up the cost, but it takes a lot longer too. In the design project we have been working on over the past week, we had it really easy. We ordered our parts on Mouser, had them delivered to the BRC, and then when our professors came to visit us, they delivered them. Even still, we had to made sure we ordered backups of each part. Otherwise, if one component failed, the project would be put on hold until the next time someone comes to Malawi.

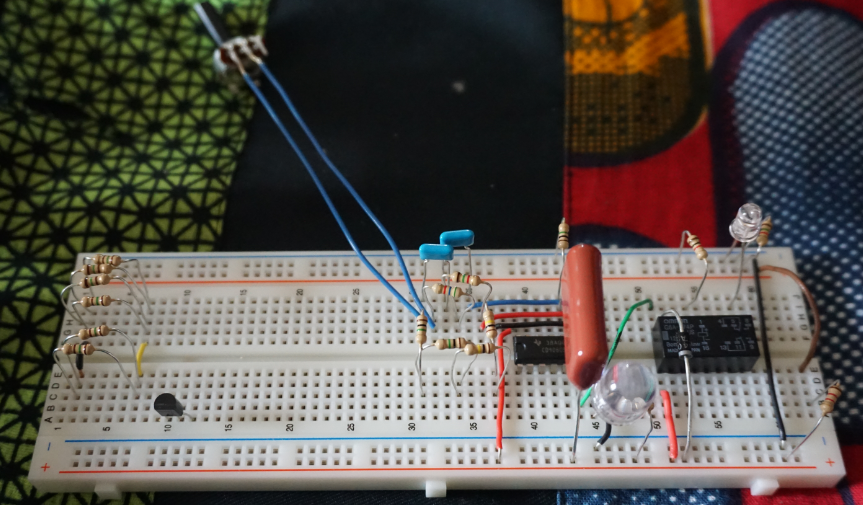

(Our prototype for the IV timer based shut-off valve)

Thankfully, the future outlook for prototyping in Malawi is improving, at least for students at the Poly. The friendship that is being formed and that will continue to grow will hopefully be a gateway for more prototyping experience for these students. This is great news for the students at the Poly who have great theoretical knowledge, but rarely get to put it into practice. The opportunity for hands on experience will take their education to the next level, making them much stronger engineers for the workforce.

I know that I personally really enjoy being able to put pieces together; that moment when the light comes on and it all works is priceless. I’m glad that I have had this opportunity to prototype a little bit in Malawi, but I’m even more glad for the hope there is that the students here will get the same opportunity.

This is the last blog of the summer for me (I write at the DC airport, almost all of the way home). It has definitely been a fantastic time as you have hopefully been able to see through the pictures and blogs. I am amazed looking back on all that we have been able to accomplish, and I am so grateful to my program directors and sponsors for making it happen.

Tionana!

(Typing out this last blog in the airport) (Biting into the first burger back in the States: two patties, bacon, cheese, pretzel bun

…it was fantastic)