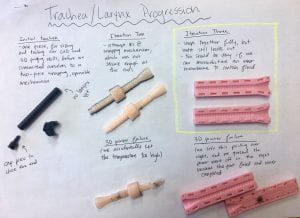

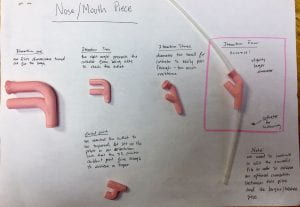

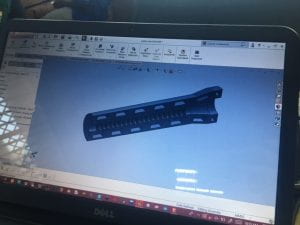

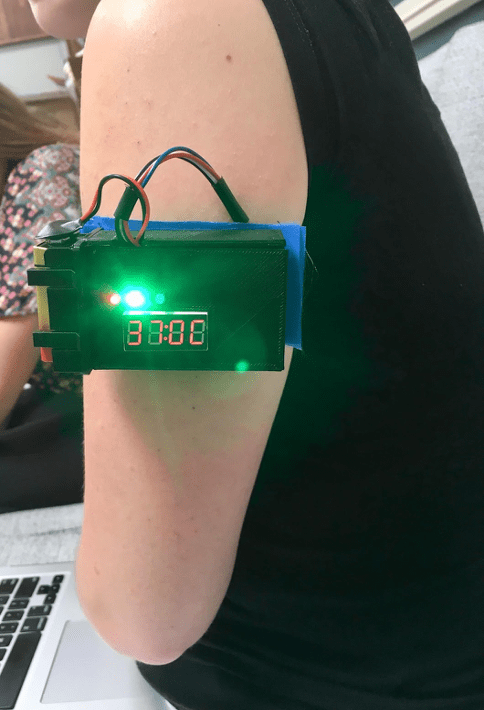

The past two weeks can be summarized by two words: rapid prototyping. Everyday, we walk into the studio with ambitious goals of finishing multiple attachments to our model, but somewhere along the line we’ll hit an obstacle. One 3D print’s dimensions are incorrect. A ball and socket fails to replicate the range of motion of a human shoulder. Our elastic strings don’t properly simulate muscle tension. But once a prototype falls short, its life is not over. We immediately begin shaving away extra material, cutting new holes, and taping on components to test potential directions that our next iteration could take. After a new low-fidelity prototype has been created from the remains of our previous failures, the cycle begins once more. We arrive at obstacles, meet to discuss the shortcomings of a design, and a new design is born. It’s kind of like the Circle of Life (sorry but I’m listening to the soundtrack of the new Lion King movie as I write this).

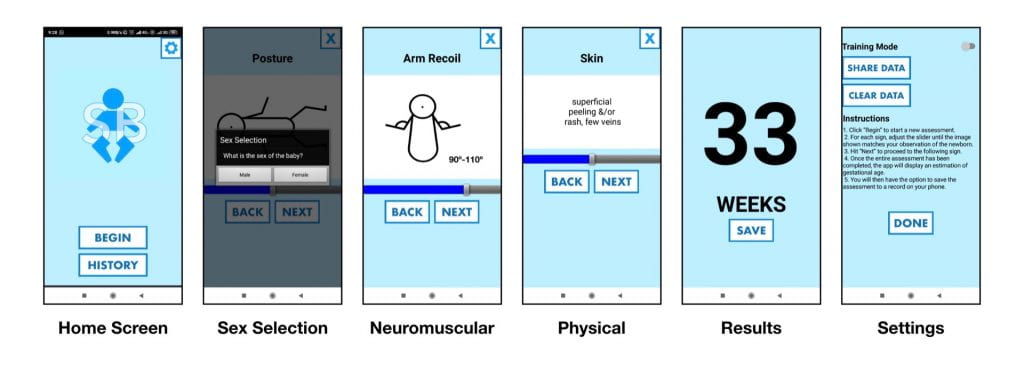

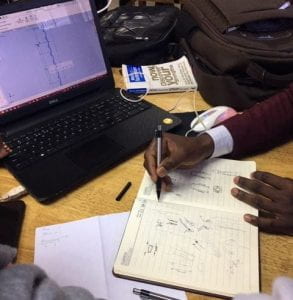

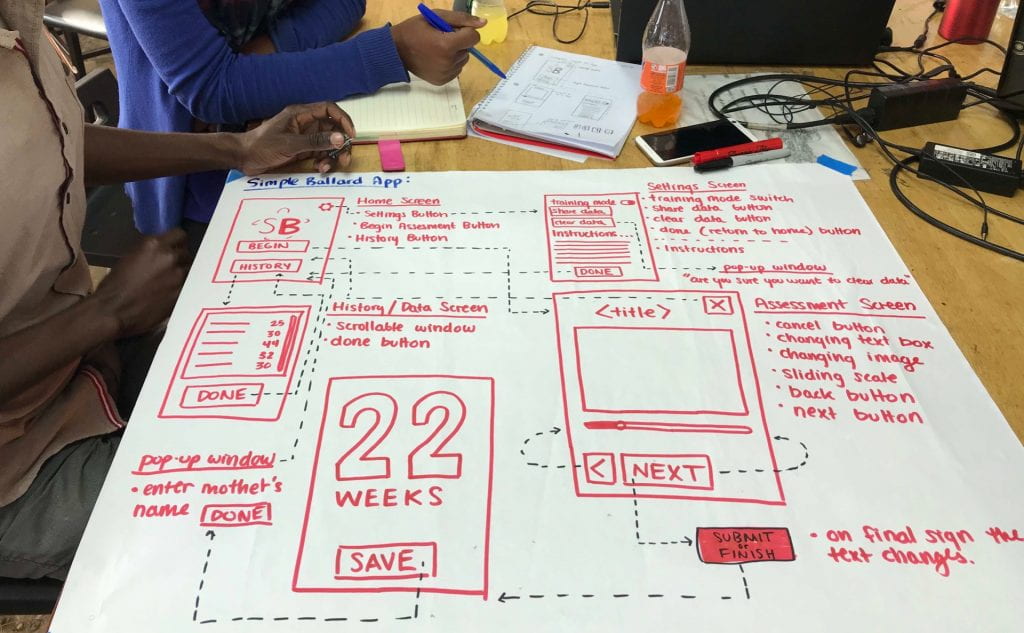

By the end of Friday, we had completed all neuromuscular attachments to our training model, and with only one week remaining, our focus shifted to developing the assessment app. In the last half hour of work before the weekend, my team grabbed a huge white sheet of paper from the back of the studio. We then began to create a flowchart, outlining the basic progression of screens within our app. Once we decided on the placement, text, and purpose for a component, I would draw it onto our plan with a vibrant red marker (I found this part super satisfying). Not only did this process help us produce complete idea of what our app would be, but every member of our team left the studio visualizing our app in the same way. In engineering design courses back at Rice, it was always stressed that a crucial step in any project is making sure all of your team is on the same page. This helps avoid any major misunderstandings later on while prototyping.

On Saturday, we drove to the Satemwa Tea plantation, the first fair trade registered tea plantation in Malawi. We began the morning with a tasting at the factory, where we each tried a spoonfuls of 18 varieties. I never knew this, but apparently even without flavoring, the different methods of rolling tea leaves have a large impact on the taste. My favorite teas were the white hibiscus, red hibiscus, green verbena, and the green mint. We then went on a walking tour through bright green rolling hills of tea plants, some of which were close to 90 years old. In the evening, we had dinner with some previous 360 interns from Malawi who had worked in Houston last fall. It was neat to compare experiences between the two different internship locations and hear about their time at Rice.

Sunday morning, Shadé and I woke up early to put finishing touches on the Clean Machine. With the craziness of prototyping our own projects, recreating this technology was a responsibility that we had pushed to the side. Taking it home to Kabula and working on it over the weekend was a good call, but looking back, we definitely had to get a little crafty with some components. For example, we completely forgot to bring the pulley’s counterweight from the US, and not being at the Poly, there was no clear replacement or way to attach the counterweight to the belt. Still wanting to test our work, we borrowed rocks from the garden and used some clothespins…

After working on Clean Machine and making a little progress on this blog, we began to prepare food for a cookout we were having with all of the interns. We underestimated the amount of time it would take to chop all of the veggies, cook the hot dogs, and fry all of the chips, samosas, and spring rolls. As a result, dinner was delayed a little, but boy was it worth the wait! I think all of us were surprised at our ability to create such a spread of food.

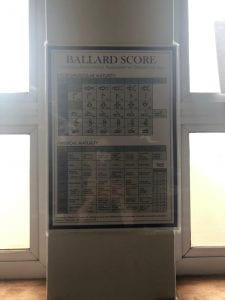

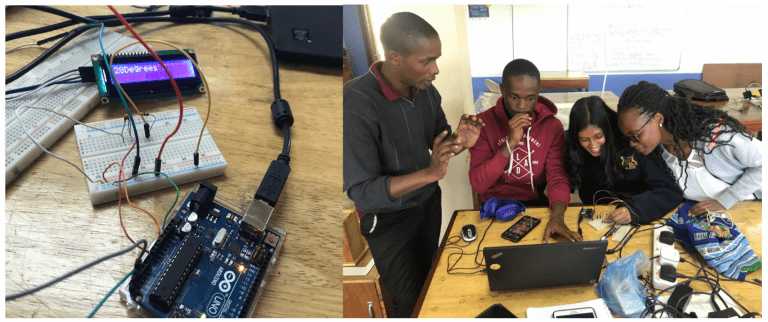

Returning to work on Monday, our team began to develop our simplified assessment app for the Ballard Score. Looking at our plan, we started with the simple stuff: creating different screens and adding in buttons. Once that was done, we had to think a little more on how we wanted to program more complicated things like our sliding scale. Being that I was the only one who had done something like this before, I initially felt as though I had to serve as a resource for the rest of my team, but this didn’t last long. I remember the moment we tested our work on a phone emulator for the first time. At that point, we had only made the buttons that switch between screens. Still, the feeling of seeing your work come to life is thrilling. Everyone soon began to practice with the program on their own time, and our team began to fly through developing the rest of the app.

Since last Thursday, we have been testing and tweaking our work. You can find our most recent version attached below. If you are viewing this blog on an android smartphone, simply download, open, and install the file to try it out!

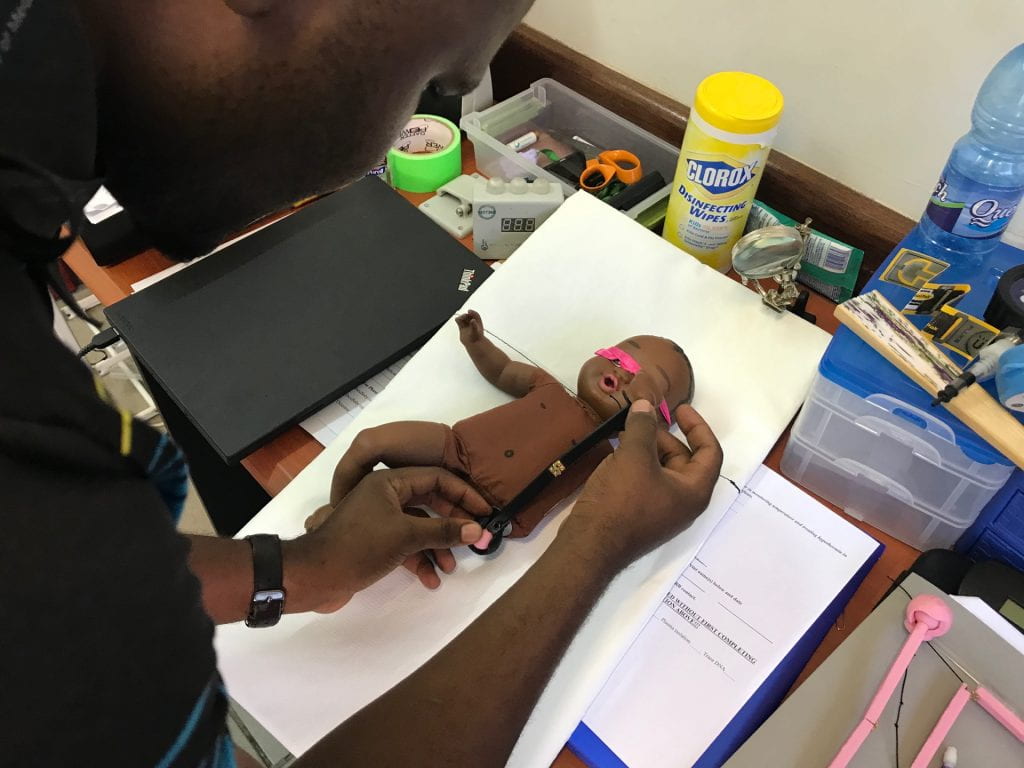

Early Friday morning, I hopped in a taxi to Queens for a meeting with Prince, a nurse who frequently collaborates with Rice360. He was able to give plenty of useful feedback for the Clean Machine prototype and even had the time to look at our new Ballard Score training model. After talking with him, I arranged to observe in the NICU for a few hours until work started at the Poly. Heading into the ward, I was very concerned about my presence becoming an obstacle for nurses to work around. This was the last thing I wanted, so I began by sitting in the corner towards the back of the room. After a short while, Sarah, a fellow at Rice 360, tapped my shoulder and told me that something was happening on the other side of the room that I might be interested in seeing. A new baby had been admitted into the high-risk section of the ward. From a distance, I saw nurses quickly retrieving equipment from all around the room. The level to which every nurse is able to work with one another is incredible. Their communication is clear, quick, and their collaboration is efficient. Observing led me to better understand the role in which an engineer could contribute in this setting.

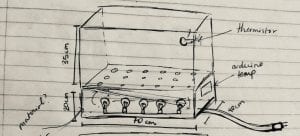

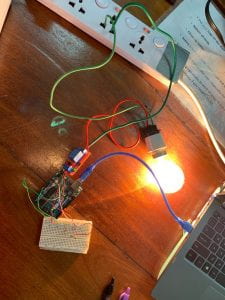

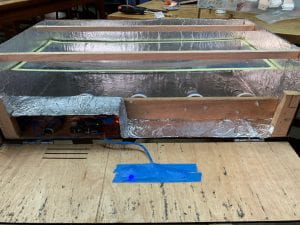

When the new baby was admitted, I saw Prince run to the other side of the room and grab a linen blanket. He then held the blanket up to a radiant warmer used to heat the room for at least 30 seconds. As I was reminded by Sarah, the best treatment for a cold baby is a warm blanket, warm socks, and warm hat. After the situation had calmed down, Prince came over to tell me that a useful project would be a warm storage container for linen blankets. This idea would save time in situations where every second counts. Prince’s suggestion got me thinking about ways to simplify processes, and I soon began to observe other opportunities for engineering to have an impact.

Recently, I’ve been thinking more and more about the scope of this program. As an intern, one of my primary responsibilities is needs-finding for projects at Rice. These projects are then worked on, and taken back for feedback. Looking forward into my next few years of education, I may even end up working on a need we identified through this internship. It truly is a cycle, involving every stakeholder at every stage. From nurses in hospitals across Malawi, to the students from four separate universities, to the professors and organizers that make it all possible, everyone is fully invested in a common goal. Step by step, prototype by prototype, progress is made, never losing sight of the bigger picture.