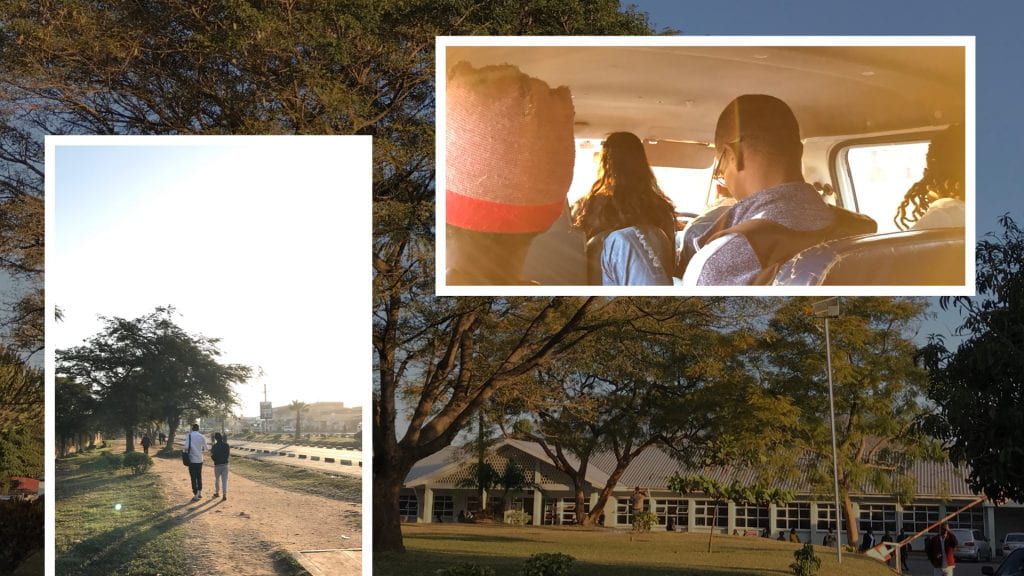

Thinking about how fast these first few weeks have flown by, it’s really hard to accept that we are halfway through this internship. Recently, I have been taking more and more pictures of regular day-to-day tasks, not wanting to forget the small things: the sunrise, the walk from Queen Elizabeth to the Polytechnic, and our home-cooked family dinners at Kabula Lodge. The following blog will take you through one day of our lives here in Malawi. I’ll walk you through decisions my team makes while prototyping, things I notice on the streets of Blantyre, and my thoughts from when I untuck my mosquito net in the morning until I tuck it back in at night. Hopefully this blog gives you a sense of what it is like to be an intern in this amazing program.

– July 5th, 2019 –

7:26 AM

It’s become kind of a tradition that every morning as we are eating breakfast, I will set down my tea and declare the time to be 7:26. The bus from Kabula leaves every morning at 7:30, and through trial and error, we’ve discovered that in order for every intern to take their seat on time, this is when we all must begin to scarf down our remaining tea and toast.

This morning the normal bus was out of service. Instead, we rode to work in a smaller replacement bus with fewer seats and unfortunately, less leg room. Once at Queen’s we began our usual walk along the busy streets of Blantyre: through the small market outside of the hospital, under the bright blue walking bridge, and between two tall palm trees marking the side entrance to the gated Polytechnic campus. From there, we usually have around 30 minutes until work starts, so we spend our time either reading or journaling in the sunny seating of an outdoor amphitheater.

8:30 AM

Wongani, a technician at the design studio, waves to us from the covered red walkway on his way to unlock the doors to the studio. Inside, light pours in through the 360º windows onto the clean and shiny tables, signaling a fresh start to a new day. While we wait for the rest of our project teams to arrive, Shadé and I make progress on the Clean Machine prototype.

9:00 AM

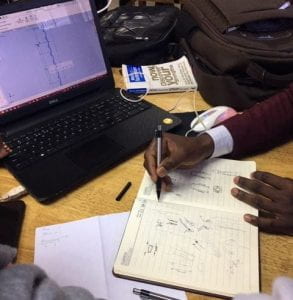

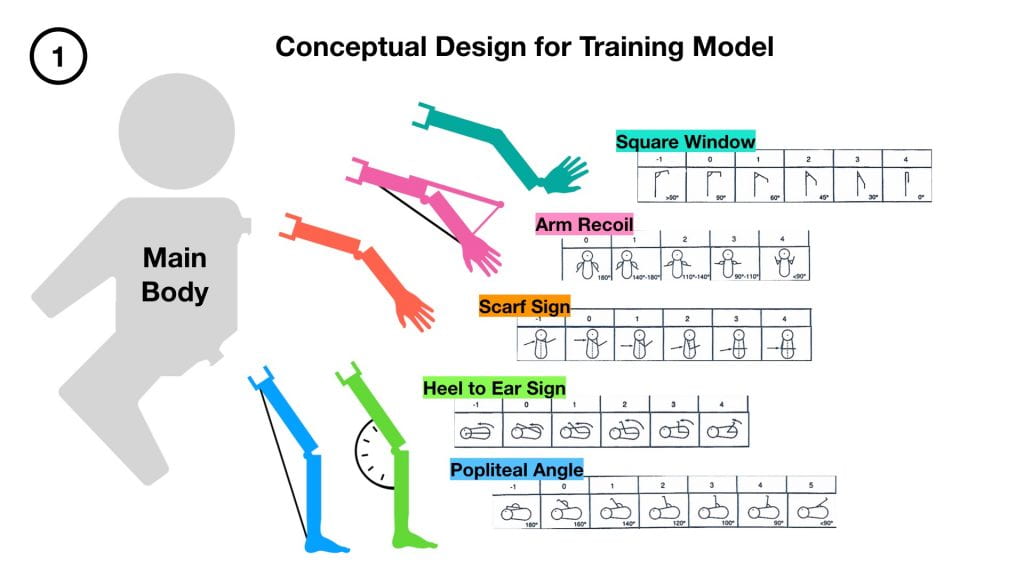

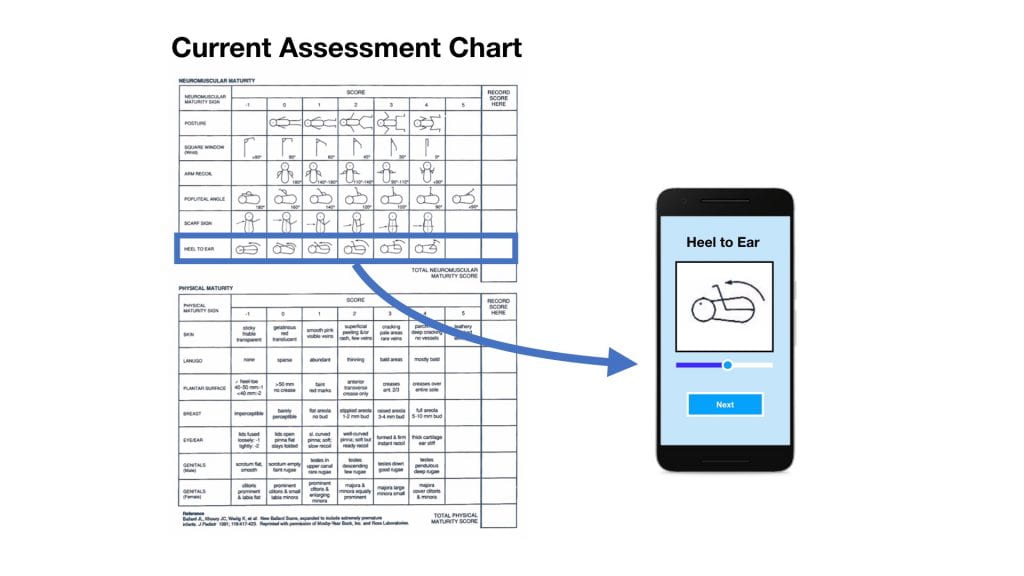

My Ballard Score team sits down and begins a brainstorming session for one of the training model’s attachments. For 10 minute intervals, we sit in silence, each writing down whatever comes to mind in our journals. At the end of the time, we each have several pages filled with a mix of potential solutions and mechanical components. Each one of these ideas is then shared with the group, free of any immediate criticism. As someone reveals a drawing, others build off of it, presenting their own related thoughts and combining concepts.

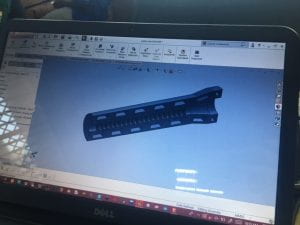

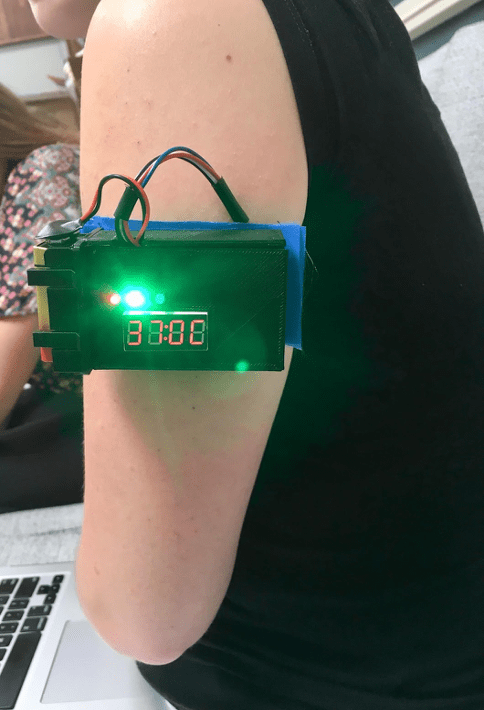

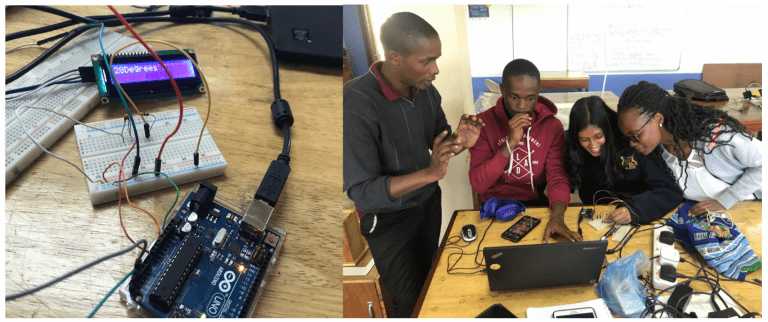

Betty and I spend the rest of the morning developing low-fidelity prototypes for two of the brainstormed ideas. While we bend pipe cleaners and straws to create proof-of-concept models, Rodrick and Racheal continue work on two other neuromuscular attachments: heel to ear and the popliteal angle. With a goal of finishing prototypes for both of these attachments by the end of the day, they make final adjustments to dimensions in various CAD files.

12:07 PM

Not wanting to waste valuable time, my team hangs back a few minutes into lunch to get our 3D prints started. With stomachs growling, we all make our way across the street to Miko’s Dessert Shop. Rather than getting their extravagant ice cream waffle cones (like we do every Friday), we instead order freshly baked cinnamon rolls. Unable to resist the smell, I finish mine on the walk to get an actual lunch from LJ’s – a small red shack across from Queen’s.

At LJ’s you get a choice of nsima or rice, a meat, and a variety of vegetables. I prefer to have nsima over rice, mainly because I think it is way more fun to eat. From what I have been taught, here’s how to best enjoy these bouncy scoops of corn flour: first roll a ball in the palm of your hand (quickly because it’s hot), use your thumb to press a hole in the center, then use the nsima as a spoon for the rest of your food.

1:30 PM

The work ethic of the Polytechnic and MUST interns is incredible. In addition to the internship, they are still attending classes, completing homework, and working on their own side projects. I honestly have no idea how they manage to do it all. Today, Rodrick had to leave for a few hours to give a presentation. In his absence, Racheal, Betty, and I have found little ways to be productive. Racheal has begun working with the software we will be using next week to design our app. Betty continues to work on her low-fidelity prototype, and I start designing components of the training model’s arms in SolidWorks.

3:30 PM

Just as bright light pours in through the windows every morning, the warm beginnings of a sunset flood the design studio starting at around 3:30 p.m. Over the past few days, I’ve begun to notice the effect of this lighting on our productivity. This final hour truly becomes a test of our willpower to accomplish the goals we established in the morning. Today, we had hoped to finish prototypes for both of the neuromuscular attachments on the hip, but as the orange tint of the sun overtakes the fluorescent blue of the LEDs, we haven’t assembled either.

When Rodrick returns from his presentation, I am staring with frustration at my computer screen, unable to get one dimension of an arm to change without having to start over again from scratch. Unlike the rest of us, he is somehow still full of energy. It spreads to the rest of us, and the next hour becomes a mad rush to finish at least one of the attachments.

4:26 PM

With 4 minutes to go before the end of the day, we have completed the prototype for the heel to ear attachment. My fingertips are encrusted in a layer of solidified super glue and our table is a mess of PLA shavings, bits of elastic, and random hand tools. During the walk back to the bus, I reflect on what we were able to accomplish.

It’s difficult setting goals and then not being able to accomplishing them fully. Back at Rice, the OEDK is just a short walk away from my dorm room, allowing me to work on a project until I am satisfied, sometimes into the early hours of the morning. Here, a 15 minute bus ride separates me and the design studio. At the end of every day, we must set down our tools regardless of whether or not we have reached a natural stopping point. As frustrating as this is can sometimes be, I feel that it has helped me to become a better teammate.

In the past, I have struggled to let others take the reins in group projects. If a calculation was being made, I wanted to double check it. If a prototyping method was modified, I wanted to be there to understand the decision. But for the first time in my life, the engineering design process has been shoved into the time constraints of a workday. With so much to do, there is no longer time for me to obsess over every detail. My group at the Polytechnic has learned to strike a balance of task-division and making sure the whole group remains on the same page.

5:30 PM

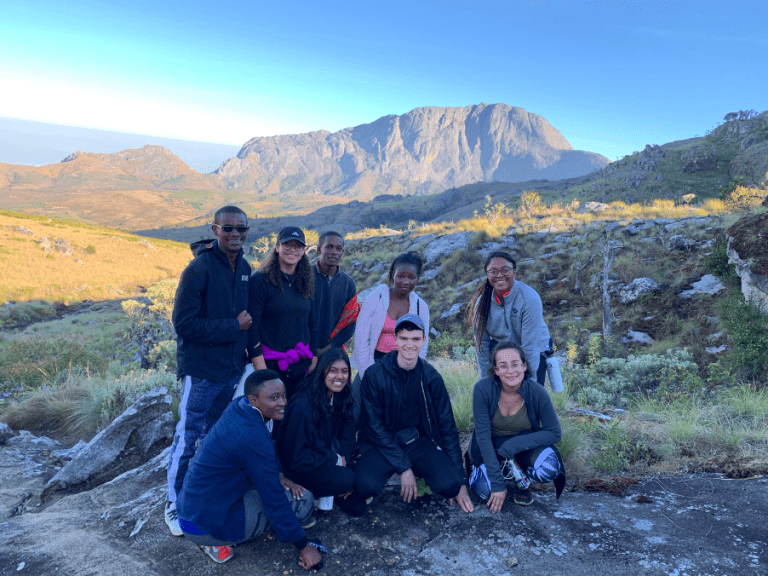

Once back at Kabula, we all walk under the beautiful orange flowers that drape over the reception area. Having done laundry the night before, I take down my clothes from the line and begin to pack for our weekend hike of Mount Mulanje. Hannah, Liseth, and Cholo start preparing dinner in the kitchen. At the very beginning of the internship, we randomly selected four teams to trade off cooking duties. The system works well and has been a fun opportunity to learn how to make some new dishes from the Tanzania interns. For our last meal, Joel taught Kyla and I how to make nsima, or as it is called in Swahili: ugali. The process turned out to be more difficult than expected and requires a lot of arm strength (more than I have), especially when you’re cooking for 11 people.

8:00 PM

Eggplant parmesan is ready. People slowly begin to crawl out of bed, up the stairs to the terrace, and take their seat around the dinner table. While eating, we joke about how we’ll probably die climbing the mountain this weekend. Liseth retells stories of Cholo’s misadventures in the kitchen. We laugh, talk, and eventually move into the lounge area. Some 0f us do research for our projects. Others snuggle up in a blanket to read a book. I begin writing.

10:00 PM

I finish this blog! 🙂

________________________________________________________________________________