After three weeks of needs finding, research, and brainstorming, we’ve finally begun to delve into the prototyping phase of the engineering design process. This week, we began to CAD parts, 3D print them, and prepare for the assembly of our prototype.

I should probably take some time to explain my team’s project, since I don’t think I’ve done that yet. We are Team Suction, and we’re working on a neonatal airway deep suctioning training model. I’ll explain what that means in a moment. My teammates are:

Napendael (Nanah) Msangi from Dar Es Salam Institute of Technology in Tanzania

Foster Sentala from Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST)

Chisomo Mbale from Malawi Polytechnic (Poly)

Different people with different levels of technical and medical backgrounds will read this blog, so I’ll take some time to explain neonatal airway deep suctioning and the approach we’re taking to developing a training model.

Sometimes, babies are born with their lungs and airways full of amniotic fluid, and this prevents them from taking their first breath. In order to remove the fluid, nurses must use a catheter and a suctioning machine. The catheter is a long, thin tube that must be inserted into the trachea of the newborn. One end of the catheter attaches to what they call a suctioning machine, which creates negative pressure in order to suck the amniotic fluid out of the airways of the newborn, enabling them to breathe. There are a few difficulties associated with this procedure. First, it is common for nurses to overestimate the amount of tubing appropriate to insert into the infant’s airways. If the tubing is not inserted far enough, not all the fluid will be suctioned out. If the tubing is inserted too far, past the trachea and into the lungs, the baby will go into respiratory arrest. The second issue is that it’s easy to traumatize the newborn’s airways with the catheter if one isn’t gentle enough. This is particularly difficult to avoid if the newborn is premature or is moving around a lot during the procedure. Trauma to the airways can cause a variety of issues, including scar tissue build-up within the airways, which could restrict breathing. For these reasons, it is critically important that nurses are empowered with the knowledge and confidence to complete this procedure carefully and effectively. My team and I have decided to develop a mannequin-style training model in order to give nurses the opportunity to get hands-on practice of this skill during their schooling years in order to gain confidence and experience before entering day one of their jobs in hospitals.

On Monday, we were able to visit the labor ward at QECH, where the deep suctioning occurs right after babies are born. We actually entered the ward right after a suctioning procedure had taken place – we just barely missed it! When we arrived, a nurse was wrapping a newly-suctioned newborn in chitenge and connecting them to oxygen.

The most valuable part of our visit was that the head nurse in the labor ward was able to show us an existing training mannequin. It’s used to teach manual airway ventilation, which is a totally different procedure from deep suctioning, but we were inspired by the model itself. It was a blow-up doll with a shell for the face and for the torso, underneath which the tubes reside. Similarly, we decided to use a baby doll. We made a plan to cut off the face and reattach it using hinges, making it able to open and close. The tubing will reside on top of the doll’s chest and underneath its clothing.

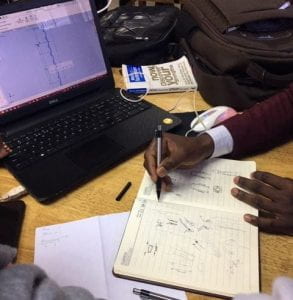

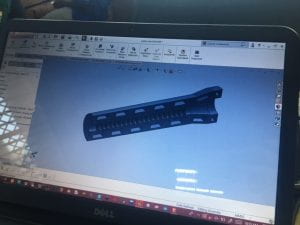

We have begun the process of creating CAD models of the tubing and airways. Foster pioneered the CADing process, since he had the most experience with Solidworks. So far, we have CAD models of the trachea, larynx, and airways to connect to the nose and mouth. We have also begun 3D printing these files. We finally managed to procure a baby doll that would work for us (shoutout to Sally for having an extra one from the Ballard Score project).

On Friday, we began to dissect our baby doll. We cut off the face of the doll, and spent far too long attempting to reattach it partially using tiny hinges. Who knew that pieces so tiny could prove infinitely more difficult to work with than their normal-sized counterparts?

Over the next two weeks, our biggest challenge will be figuring out how to mimic the trauma that can be caused by suctioning. We want nurses to practice on the model and know when they have not been gentle enough. Therefore, we want to include some sort of membrane which ruptures when too much force is used. The membrane would then be removed and observed in order to inform nurses whether they made a mistake. We are considering different approaches to manufacturing this rupturable membrane. Hillary recommended the use of a thin plastic such as tephlon, which could be cut into small strips and secured together at the ends to create a cylinder. I am also exploring the option of molding and casting using a delicate type of silicone. Unfortunately, we don’t have the ability to special order unique types of silicone molding and casting materials, so we’ll have to improvise if we go this direction.

Overall, I’m thrilled to have finally entered the prototyping stage. As critical as I believe the first steps in the design process are, they can feel arduous. There’s a certain exhilaration that comes during prototyping. It feels powerful to be able to turn the ideas we’ve been discussing for weeks into physical realities. This must be what it feels like to be an engineer.

BONUS CONTENT