Part 1: Healthcare Disparities Here, There, and Everywhere

I’ve spent most of last week analyzing monitoring data for the PUMANI bubble CPAP in hospitals throughout Malawi. I was tasked to use the data to create graphs looking at the impact of power outages, time of death, temperature, and weight on mortality rates of CPAP. In addition, I was told to make separate graphs for this data for the hospitals in the Ministry of Health (MOH) system and the Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM system) since they are given separate reports. (MOH hospitals are public, government run hospitals that offer all services free of charge, serving 63% of the population while CHAM hospitals are private not for profit hospitals that serve 37% of the population.)

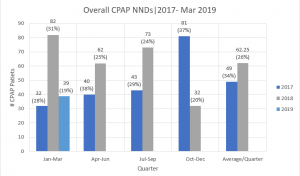

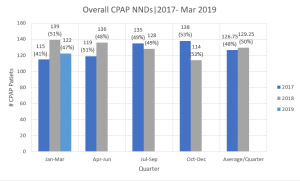

While this technically wasn’t something I was analyzing, what surprised me most was that the overall mortality of CPAP patients in CHAM hospitals was consistently lower at 20-30% than that of patients in MOH hospitals at 40-50% over the last two years. In addition, the mortality rates were consistently decreasing, and the number of patients put on CPAP was consistently increasing across quarters in the CHAM system while this fluctuated a lot for MOH hospitals. (This part may, however, be partly attributed to the fact that CPAP was introduced quite recently in CHAM hospitals and longer ago in MOH hospitals.) This suggests that private hospitals in Malawi provide better quality healthcare than public hospitals. (Granted, this is a relatively limited set of data covering only CPAP patients and looking only at the past 2 years). While technically CHAM hospitals only charge “nominal” user fees to cover the cost of operations, when explaining the healthcare system to me last week, Rodrick (the Poly intern who used to be a data clerk at a rural health center) seemed to imply that the fees were still exorbitant for most people, which I also read online. This public-private divide in healthcare reminded me of that in the United States.

While the most apparent or, at least, the most discussed issue on the political stage regarding healthcare in the U.S. is the lack of affordability, another important factor that should garner more attention is the quality of the publicly subsidized healthcare that exists. For example, the quality of healthcare available at Ben Taub Hospital—a hospital that is part of the Harris County Health System and offers local and state level programs to help subsidize the costs of services for low income patients—is, to some extent, different from other hospitals in the Texas Medical Center. For instance, I remember our mentor for the Ballard Score training model project last semester—a neonatologist at the Texas Children’s Hospital—telling use that while the Ballard Score never needs to be used at TCH due to the abundance of prenatal care (including early ultrasounds that allow gestational age to be tracked) that expectant mothers receive there, it was actually, to her knowledge, used occasionally at Ben Taub since patients there have less access to prenatal care. Additionally, I remember one of my friends who volunteers there said that patients could occasionally be in the waiting room for twenty something hours before being able to see a doctor due to relatively low doctor to patient ratio. (This congestion is also a problem that occurs in Malawi by the way—the courtyards at QECH are filled up with families waiting for long periods before they receive treatment.) (Also, this is not to say Ben Taub is not an outstanding hospital by any means. When I was reading about the hospital online, I found out it was one of only three level 1 trauma centers in the TMC and had earned numerous awards.)

Anyways, this led me to think about other disparities in healthcare that Malawi and the U.S. have in common: namely, the difference in care available in rural and urban areas. In Malawi, the healthcare system has multiple tiers providing different intensities of care. At the top are the five central hospitals located in major cities (QECH being one of them) that serve as tertiary center with many specialties available including functional operating theaters. Under that are the district hospitals for the 27 districts, which serve as secondary centers. Because the healthcare system is structured such that the available (and relatively limited) resources (both equipment and human resources) first fulfill the needs of central hospitals before the other tiers, there are substantially less resources in district hospitals. As one nurse put it when we visited the Mulanje District Hospital, they only treat the conditions that they are able to treat there—an understandable statement considering they have no incubators, one radiant warmer that was not working during the visit, and even an occasional scarcity of thermometers. The trickle down model of resource distribution even more so affects rural health centers that have very, very few resources. As Rodrick said and I later read online, these have only a few nurses—sometimes even just one as Rodrick stated—and often no clinicians. While the CHAM hospitals aim to fill this gap of healthcare availability in rural areas, as previously stated, the costs are often prohibitive.

Although the U.S. does not have a centrally mandated healthcare system that purposefully imposes this type of disparity and admittedly has a lot more resources overall, this disparity between healthcare in rural and urban areas still exists. I honestly was not aware of this (and I suspect a good portion of the general public also isn’t) until Dr. Sonia Parra’s lecture on LUCIA—a training modeled designed by Rice 360 to improve cervical cancer screening and treatment—in the Introduction to Global Health course. It surprised me so much to learn that, like many lower resource countries, the Rio Grande Valley—located in the same state as the world’s biggest medical center—has a high incidence of cervical cancer due to the lack of availability of screenings for HPV. To further emphasize this rural-urban divide in healthcare, statistically speaking, the doctor to population ratio is almost 2.5 times higher in urban areas (at 31.2 physicians per 100,000) compared to rural areas in the U.S. (at 13.1 physicians per 100,000). The commonality in the health disparities between Malawi—with a government run healthcare system—and the U.S.—with an almost entirely privately controlled healthcare system—show that the question we should be asking about healthcare policy is not merely how do we make healthcare affordable and available for all in the U.S. but how do we make high quality healthcare affordable and available truly for all on a global scale.

Sources:

http://www.health.gov.mw/index.php/2016-01-06-19-58-23/national-aids

https://www.malawiproject.org/zzz/hospitals-healthcare/

https://www.harrishealth.org/locations-hh/Pages/ben-taub.aspx

https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/about-nrha/about-rural-health-care

Part 2: Fun Pictures from this Week

I realize this was more of an op-ed than a blog, so here’s some fun pictures (and captions) highlighting last week’s adventures.