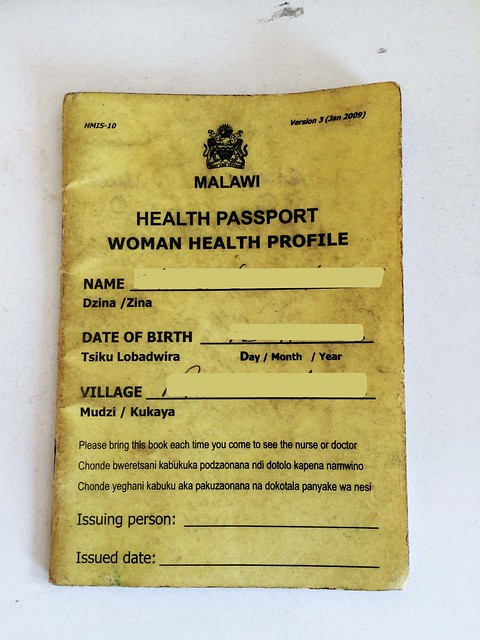

It’s not uncommon to run into foreign doctors in every ward at Queens. Since it is a teaching hospital associated with the College of Medicine there are numerous foreign doctors, visiting professors, and researchers roaming the halls. It’s great to have so many varied, international perspectives, but it also makes doctor-patient communication very hard. A lot of the patients at QECH know little to no English, and doctors’ inquiries into their complex medical histories are usually met with blank stares or detailed explanations in rapid Chichewa. So when their limited grasp of the local language fails them, the doctors flip through the patient charts and find the small, meticulously-kept, well-worn yellow booklets that act as windows into the lives and medical issues of each patient. These Health Passports are a health management information system that chronicles the check-ups, hospital visits, laboratory test results, and health conditions of each Malawian.

|

|

Given free to newborns or purchased for 200 kwacha (about $0.50) by everyone else, the passports are a great way to manage patient care collaboratively across institutions in the Malawian healthcare system. Since there are no standardized electronic systems that would allow hospitals to share electronic medical records (EMRs) with each other, the patient acts as the messenger, in charge of caring for and presenting the Health Passports at each medical visit.

It’s not always a perfect system. Often health centers forget to conduct routine tests or record the results of those tests in the health passports, which means doctors have to diagnose and treat patients using incomplete information. Yet, even with some holes in information, the health passports are invaluable in bridging language barriers and in providing a comprehensive report of patient history.

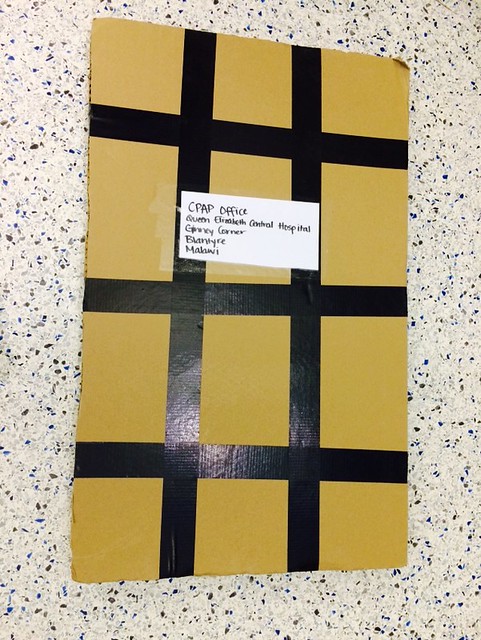

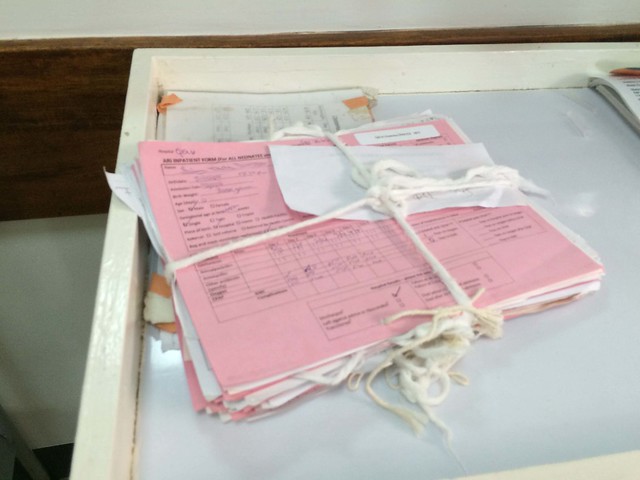

Once health passports are brought to hospitals, they’re incorporated into the medical charts for the patient. These charts include referral forms from other hospitals, basic information about the patient, surgical updates, doctors’ notes, and more. Since staples are at a premium here, gauze is used to hold the records together and the charts are usually placed wherever there is space (walls, sinks, hanging nails). Sometimes this leads to misplaced files in the hospitals. Karen and I talked to a few doctors and nurses about this problem and came up with the idea of putting laminated folders on the walls next to each patient bay as a chart holder. It’s an exceedingly simple solution, but we hope it will make the jobs of the doctors and nurses just a little bit easier. So far we’ve made one chart holder as part of a trial run and have seen a lot of excitement from the nurses in the ward, which hopefully means that we can start expanding this to more patient bays.

|

|

Chart holders may be a stopgap solution, but the bigger problem at QECH and other hospitals is the lack of storage space and organizational materials to help keep track of patient records. Already, nonprofits like Baobab Health Trust are encouraging longer term solutions–in Baobab’s case they do this by creating EMR systems out of recycled computers. At Queens we saw another newly implemented electronic system that creates international birth certificates for babies born in the hospital. The Malawian healthcare system has been fairly slow in the uptake of some of these electronic systems, but as momentum begins to build, telecommunication infrastructure improves, and computer literacy grows, it is increasingly likely that battered charts held together by tenuous ropes of gauze will become a thing of the past.

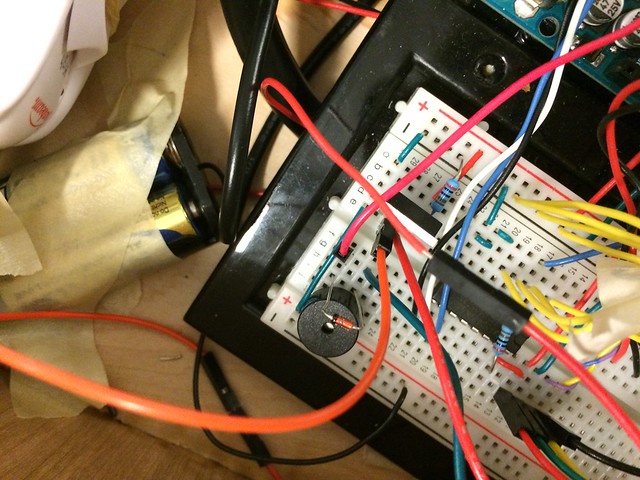

e had the help of some experienced engineers.Even when one of the main electronic parts in the device broke down, the Poly students were able to find a way to continue testing the circuit by using a simple LED as an indicator for whether the device was functioning correctly. It’s these kinds of skills that go beyond theoretical classroom knowledge. Their talent is something born of interacting with machines hands-on–putting them together and breaking them down to understand how they work. It’s also this kind of talent that can lead to out-of-the box innovations that have kanju written all over them.

e had the help of some experienced engineers.Even when one of the main electronic parts in the device broke down, the Poly students were able to find a way to continue testing the circuit by using a simple LED as an indicator for whether the device was functioning correctly. It’s these kinds of skills that go beyond theoretical classroom knowledge. Their talent is something born of interacting with machines hands-on–putting them together and breaking them down to understand how they work. It’s also this kind of talent that can lead to out-of-the box innovations that have kanju written all over them.

Polytechnic. Physical Assets Management (PAM) is a department housed at Queens that maintains the medical equipment at hospitals across Malawi. They are currently a graveyard for broken equipment that can’t be fixed for lack of appropriate parts and adequate budget. The picture to the left shows one of PAM’s many shelves of machines awaiting repair. We hope to create a collaboration between the new Biomedical Engineering program at the Polytechnic Institute and PAM so that engineering students have a chance to do hands-on engineering work with the broken machines at PAM and PAM has a chance to benefit from the innovative ideas of these students. Though the idea is still in development, we hope it can be a mutually beneficial arrangement that utilizes kanju to create a sustainable cycle of problem-finding and solution-engineering between PAM and the Poly.

Polytechnic. Physical Assets Management (PAM) is a department housed at Queens that maintains the medical equipment at hospitals across Malawi. They are currently a graveyard for broken equipment that can’t be fixed for lack of appropriate parts and adequate budget. The picture to the left shows one of PAM’s many shelves of machines awaiting repair. We hope to create a collaboration between the new Biomedical Engineering program at the Polytechnic Institute and PAM so that engineering students have a chance to do hands-on engineering work with the broken machines at PAM and PAM has a chance to benefit from the innovative ideas of these students. Though the idea is still in development, we hope it can be a mutually beneficial arrangement that utilizes kanju to create a sustainable cycle of problem-finding and solution-engineering between PAM and the Poly.