This week, my team had the chance to present at the first ever Malawi Innovation Pitch Night, and after the whole experience, I realized how little I have written about my main project in this blog. As a result, the following post is gonna be a little more technical so brace yourself for some facts and figures, but I promise every one of them is important. I’m super excited about the work we’ve been doing so far and its potential impact so please continue reading! 🙂

Around the world, premature birth is estimated to be responsible for 35% of all neonatal deaths, mostly concentrated in developing countries. In many government hospitals in Malawi, nurses lack a systematic approach to identifying prematurity in newborn babies. Instead, birthweight, an inaccurate estimate of gestational age, is primarily used. In some cases, a reliable number can be calculated from the mother’s last menstrual period (LMP), but frequently no record is kept of this information. Rather than using birthweight, and in cases where the LMP is not known, a Ballard Score assessment should be performed. The Ballard Score is a set of 12 neuromuscular and physical signs that when combined, produce an accurate estimate of gestational age. However, even in hospitals where nurses have knowledge of this assessment, it is almost never performed.

Wondering why this was, our team traveled to hospitals all over Malawi: Mulanje and Zomba District Hospitals, and this week, Kamuzu and Queen Elizabeth Central Hospitals. From talking with nurses, we identified two obstacles that make it difficult to complete the assessment for each and every newborn…

- Many nurses lack the necessary knowledge to perform the assessment, especially in the case of the challenging neuromuscular procedures. Some nursing students told us the Ballard Score was only a single lesson during one day of their schooling, taught through pictures of the procedure rather than hands-on practice.

- Nursing teams are often understaffed and short on time. As it stands, the Ballard Score assessment takes 15-20 minutes to both perform all 12 procedures and calculate a final score. This is too long for many hospitals where as many as 20 babies are born per day needing individual care and attention.

Looking at the factors surrounding these two separate problems, my team has developed two separate solutions…

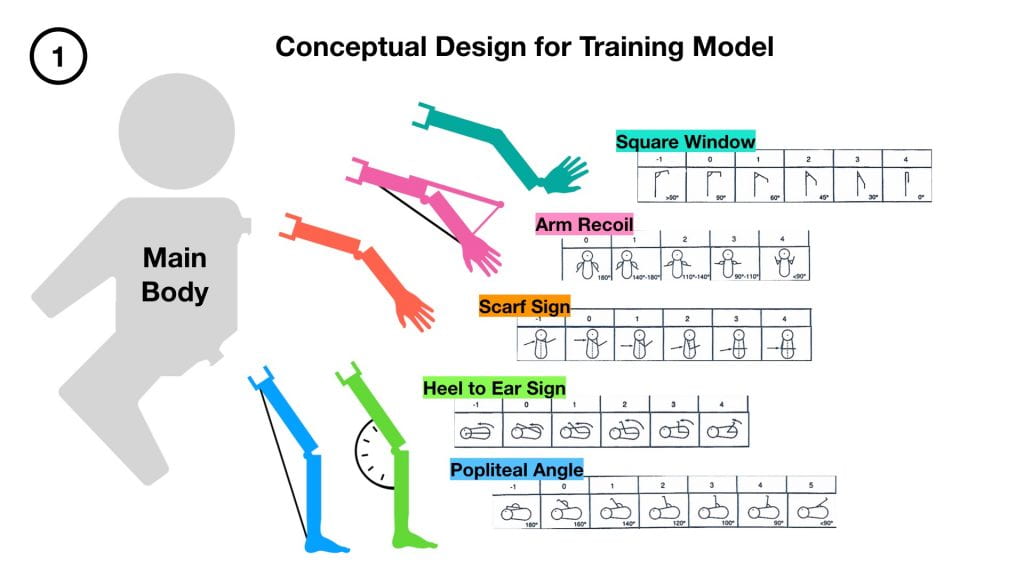

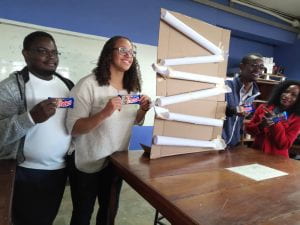

Our first design, a training model for neuromuscular Ballard signs, aims to tackle the knowledge gap between the classroom and the assessment room. The model consists of a main baby mannequin with two attachment points for interchangeable limbs: one at the shoulder and one at the hip. Each interchangeable limb corresponds to a different neuromuscular sign, and can be adjusted to replicate the muscle behavior of a baby at different degrees of prematurity.

Once fully developed, we hope to implement our model as a teaching tool for nursing schools. Imagine a classroom filled with groups of students, each gaining hands-on experience through the use of our model with different attachments. A professor could walk around from station to station, providing advice and corrections for each of the different signs as they see the motions performed right in front of them. Ultimately, the model should provide nurses with the confidence to complete the assessment when working in a hospital setting.

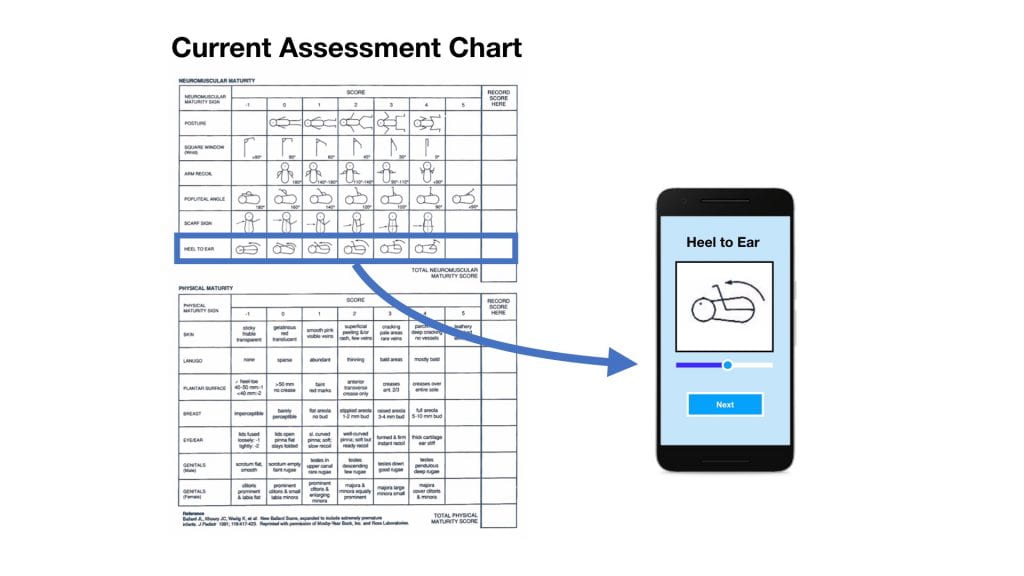

Our second second design aims to reduce the time required to perform a full Ballard Score. Having not conducted years of research like Dr. Ballard, there is no way we could remove any signs from the assessment while still maintaining an accurate estimate of gestational age. Instead, we decided to cut down the amount of time it takes to record and calculate a result from the assessment while also making it quicker and easier to match observations to the score’s criteria.

In every hospital we visited, nearly every nurse carries a smartphone. After seeing this, we determined that one of the easiest ways to roll out our design to as many hospitals as possible would be through app development. Designing an app also allows for a user interface that cuts out a lot of the unnecessary information on the current assessment chart. Numbers are cut out entirely, as all calculations are performed in the background, simply producing an accurate estimate of age at the end of each assessment. Furthermore, the use of a sliding scale takes the diagrams of each sign in the current chart and consensus them into one changing image, letting nurses easily scroll until the image matches their observation of the real baby.

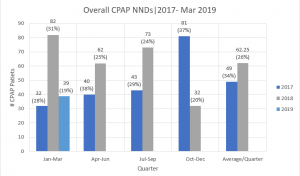

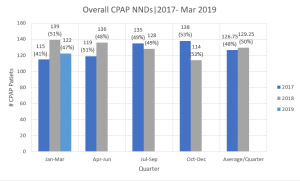

So many aspects of care for premature babies revolve around knowing their specific age. In addition to helping nurses save these precious lives, we believe our project has the potential to contribute to an even greater picture. Organizations such as Nest360º rely on accurate data when measuring the impact of their technologies on neonatal outcomes. With the most common estimate of gestational age being birthweight, reliable data surrounding premature births is difficult to obtain in developing countries. Furthermore, the paper records of many hospitals are either non-existent for individual births or difficult to sort through. Together, our training model and assessment app for the Ballard Score can become the start of a solution.

We fully realize that any prototypes we come up with in the next few weeks will no more than scratch the surface of this issue, but it is the potential for future work that excites me. What if the app could upload each assessment to a database? What if that database could be used to assess the impact of lifesaving technologies? What if that data revealed a need that had previously gone unidentified? By creating a solid foundation for others to build off of in the future, I feel that my team has an amazing opportunity to start something that truly matters.

– Alex

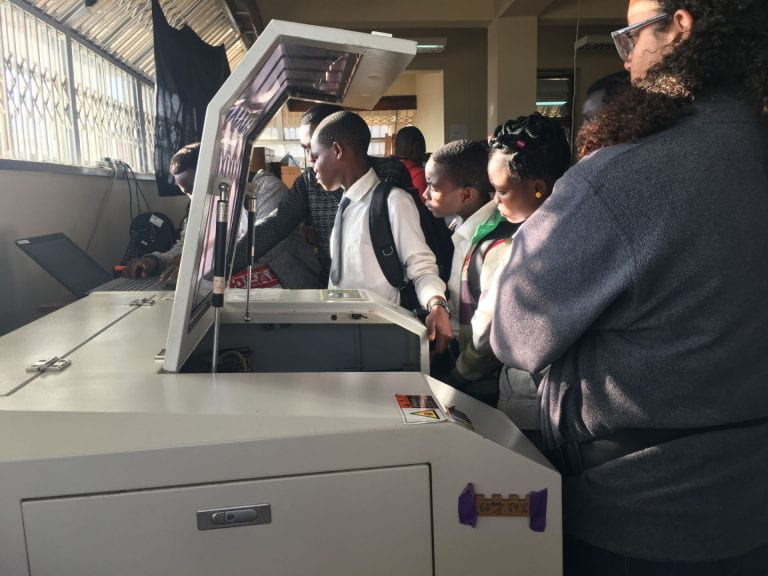

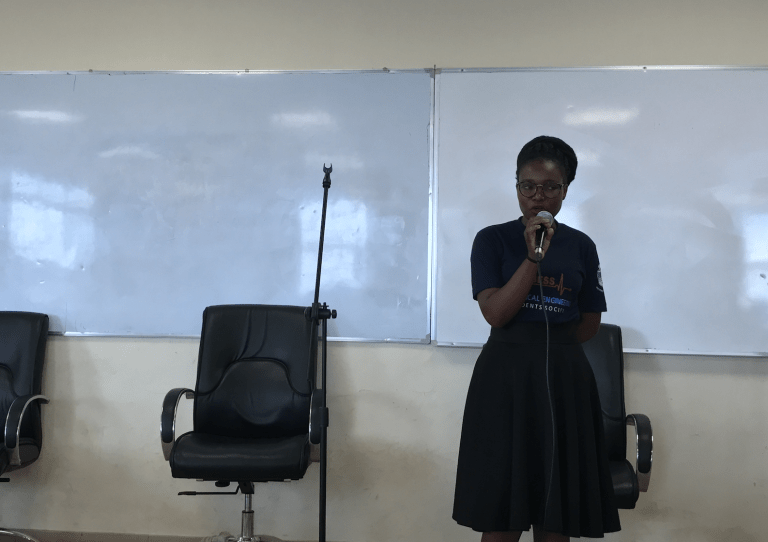

Bonus: Here’s some pictures from the rest of this week’s adventures…