Guidelines are a pretty big institution in the field of medicine. They help doctors identify a course of treatment or set the baseline for the standard of care for a certain condition. They are usually developed after much research and experimentation. They are widely respected in the medical community. The problem is that most of these guidelines just don’t work in low-resource health settings. In conversations with doctors and nurses at Queens, there have been quite a few instances that have illustrated how guidelines go awry on the ground.

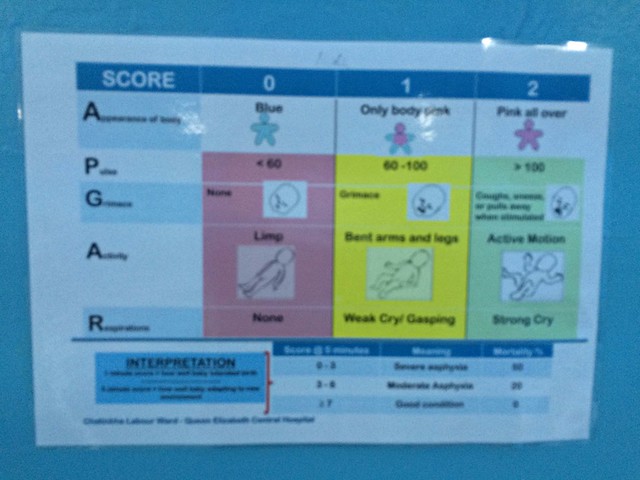

APGAR Scores

APGAR scores are used to rate the condition of a baby 1 and 5 minutes after delivery. APGAR is an acronym for Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration. In each of these categories, the baby can get a score of 0, 1, or 2 depending on how well they’re doing. Here’s a (somewhat blurry) picture of APGAR guidelines posted in the Maternity Ward.

APGAR scores can be useful in identifying the health status of the baby, but at QECH, given the high volume of babies with Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) and Birth Asphyxia, APGAR scores are often irrelevant and aren’t recorded very consistently. Babies who are blue and barely breathing spur the midwives into action as they try to save the baby rather than record an APGAR score. This doesn’t mean that they’re flaunting protocol on purpose. Rather, it means that they are overstretched and usually don’t have the time to consider APGAR scores when there are multiple complicated deliveries happening at the same time.

Putting Patients on CPAP

Infants with RDS are generally supposed to be put on CPAP. However, a lot of hospitals with the Pumani bCPAP have subpar rates of infants with RDS who are actually put on CPAP. At the CPAP coordinator meeting, some of the coordinators mentioned that CPAP isn’t used in their hospital because nurses feel uncertain about the machine despite detailed guidelines from the CPAP Office about when and how to use the device.

More worrying, however, was one presentation from Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH). The coordinator from KCH said that the Pumani CPAP was not used at all in the month of January because a few foreign doctors did not think the machine worked effectively (based on their expert opinion rather than evidence), and did not put their RDS patients on CPAP. Though these doctors were eventually convinced of the benefits of the Pumani, this situation highlights a serious problem. Both Alfred and Norman (our Ministry of Health partners) harped on the lack of national guidelines on the standard of care for certain conditions. They explained that each hospital largely sets its own guidelines. This makes it easier for visiting doctors to question the system and try to change practices that have been proven to be effective and useful on the ground.

NICE Guidelines for Inducing Labour

One of the most interesting and challenging dilemmas I have heard about during this internship concerns the practice of inducing labour in mothers. Last week, we got the chance to sit in on a Maternal and Child Mortality Morning Meeting–a special session where doctors from Paeds and Maternity came together to discuss best practices and areas of improvement. A big topic of conversation was the NICE Guidelines on labour induction, which outline the situations in which inducing labour is a good idea. These include a setting with adequate “safety and support procedures,” “facilities… for continuous electronic fetal heart rate and uterine contraction monitoring,” and “availability of pain relief options.”

The problem is that in the Delivery Suite, many of these conditions cannot be met. Yet there are mothers who are post-term or have complications and need to deliver their babies as soon as possible in order to protect the health of both the mother and the child. These aren’t isolated occasions either. Often, many mothers in the ward on a particular day have to be induced. However, given the limited equipment and staff, inducing all of these mothers at the same time can also be a disaster. It’s a fine balance. On the one hand, clinicians don’t want to induce labour unless they know they can give mothers an appropriate level of individualized care. On the other, not inducing these mothers could lead to more complications and bad outcomes for all parties involved. It’s a dilemma that makes the NICE Guidelines a nice guideline, but an unhelpful standard in a ward that has its hands tied by a lack of resources. Instead of looking at the guidelines, nurses and clinicians make their decisions on a case-by-case, day-by-day basis–a method that is occasionally successful and always stressful.