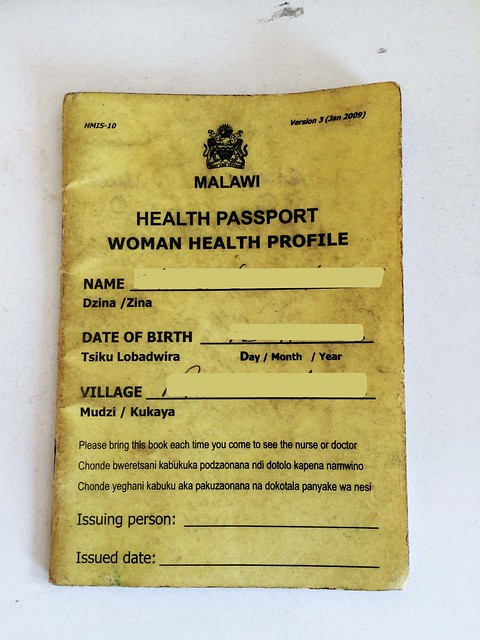

It’s not uncommon to run into foreign doctors in every ward at Queens. Since it is a teaching hospital associated with the College of Medicine there are numerous foreign doctors, visiting professors, and researchers roaming the halls. It’s great to have so many varied, international perspectives, but it also makes doctor-patient communication very hard. A lot of the patients at QECH know little to no English, and doctors’ inquiries into their complex medical histories are usually met with blank stares or detailed explanations in rapid Chichewa. So when their limited grasp of the local language fails them, the doctors flip through the patient charts and find the small, meticulously-kept, well-worn yellow booklets that act as windows into the lives and medical issues of each patient. These Health Passports are a health management information system that chronicles the check-ups, hospital visits, laboratory test results, and health conditions of each Malawian.

|

|

Given free to newborns or purchased for 200 kwacha (about $0.50) by everyone else, the passports are a great way to manage patient care collaboratively across institutions in the Malawian healthcare system. Since there are no standardized electronic systems that would allow hospitals to share electronic medical records (EMRs) with each other, the patient acts as the messenger, in charge of caring for and presenting the Health Passports at each medical visit.

It’s not always a perfect system. Often health centers forget to conduct routine tests or record the results of those tests in the health passports, which means doctors have to diagnose and treat patients using incomplete information. Yet, even with some holes in information, the health passports are invaluable in bridging language barriers and in providing a comprehensive report of patient history.

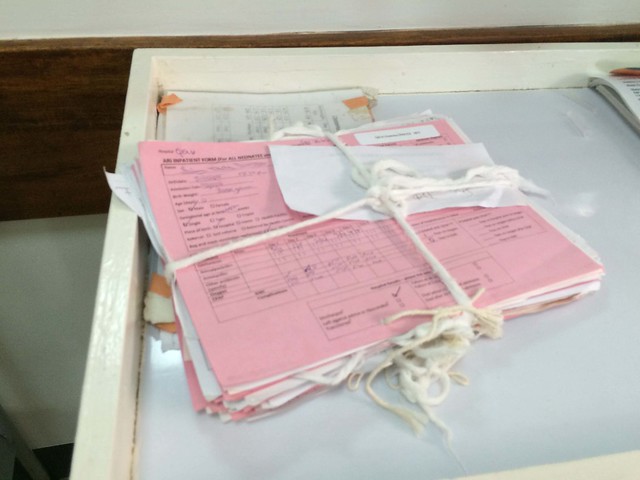

Once health passports are brought to hospitals, they’re incorporated into the medical charts for the patient. These charts include referral forms from other hospitals, basic information about the patient, surgical updates, doctors’ notes, and more. Since staples are at a premium here, gauze is used to hold the records together and the charts are usually placed wherever there is space (walls, sinks, hanging nails). Sometimes this leads to misplaced files in the hospitals. Karen and I talked to a few doctors and nurses about this problem and came up with the idea of putting laminated folders on the walls next to each patient bay as a chart holder. It’s an exceedingly simple solution, but we hope it will make the jobs of the doctors and nurses just a little bit easier. So far we’ve made one chart holder as part of a trial run and have seen a lot of excitement from the nurses in the ward, which hopefully means that we can start expanding this to more patient bays.

|

|

Chart holders may be a stopgap solution, but the bigger problem at QECH and other hospitals is the lack of storage space and organizational materials to help keep track of patient records. Already, nonprofits like Baobab Health Trust are encouraging longer term solutions–in Baobab’s case they do this by creating EMR systems out of recycled computers. At Queens we saw another newly implemented electronic system that creates international birth certificates for babies born in the hospital. The Malawian healthcare system has been fairly slow in the uptake of some of these electronic systems, but as momentum begins to build, telecommunication infrastructure improves, and computer literacy grows, it is increasingly likely that battered charts held together by tenuous ropes of gauze will become a thing of the past.